After the Austrians were pushed back in 1791—a moment that would bring the war with the Turks to an end (through the Treaty of Sistova)—many brave soldiers treated themselves to a triumphant excursion beyond the mountains. Among them was Captain Andrei Brutaru of Craiova.

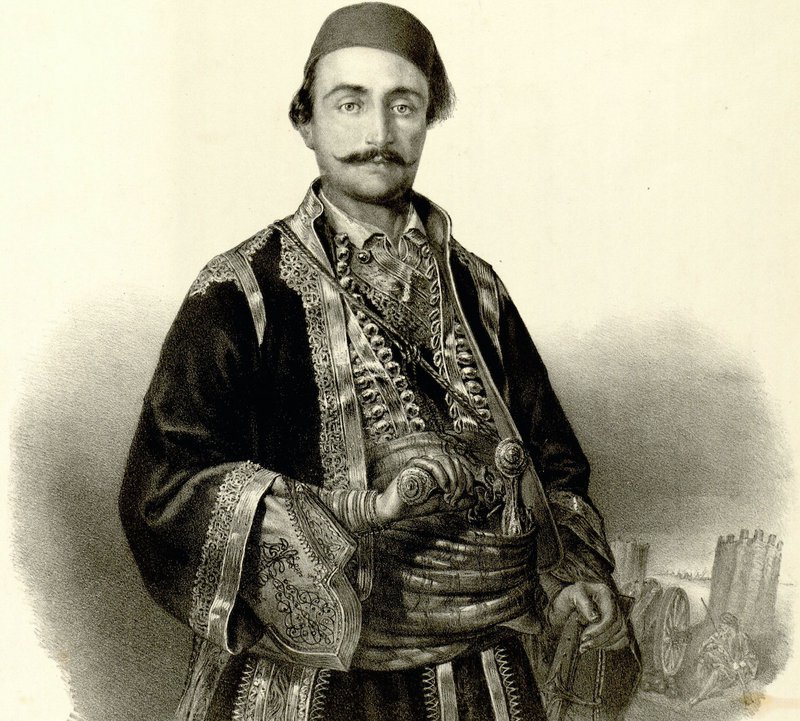

A charismatic man with electric eyes and an imposing figure, Andrei lived in Valea Vlăcii and remained, to this day, a familiar name among those who have entered local history. Not for feats of arms, but for spiritual—let’s call them—feats. When I first read about him, Veliku came to mind, a haiduc from across the Danube immortalized by Iovanovici (I place him above so we can share an image), but as I read on I realized Brutaru belonged to that rare category: the kind of man who catches your eye instantly, no matter how large the crowd.

Dressed up in German clothes and loud in the mouth, he naturally had enormous success with women. Returning from the campaign against the Germans, on friendly terms with Asechi Kara-Mustafa (who led the Ottoman troops), he built a reputation as a lover who left deep traces from Brașov to Craiova. The road home from war is always strewn with feasts and shady stopping places—in short, with wine and women.

But even once he reached home, his conquests continued. He became the most sought-after man in town. Women queued at his gate, and it became a matter of prestige to exchange at least two words with him. Some claimed to wear a shawl torn in the heat of battle from a German’s neck; others boasted of rings brought from Transylvania, or wigs received as gifts from the great captain—who had plundered the towns of the defeated and returned with unimaginable objects: bracelets painted with fairy eyes, music boxes, little devils the size of walnuts that came alive once you made a wish, shoes made of cat leather, silver teaspoons with dragons on their tails, and potions that made you loved and rich.

But among all those war trophies there was one without equal: a bewitched hand.

No one knows how or from where, but Captain Brutaru had acquired a saint’s hand, around which countless rumors began to circulate. And thieves—real thieves, the kind who believe in miracles and in hands that open locks—started prowling around Valea Vlăcii.

And now, to give you a sense of scale: a splinter of bone, a scrap of skin stuck to the bottom of a box, even a thread that had once rested on a saint’s shoulder—such tiny relics could heal illness, summon voices from the other world, fulfill modest wishes. So imagine a whole hand! A saint’s hand could do anything. That is why the captain—dressed in Ottoman finery, topped with German hats, carrying a cleaver and foaming scarves—quickly became a neighborhood celebrity.

At the same time, in Craiova there lived a protosinghel—a high-ranking priest, nearly an archimandrite—a scholar famous for his writing, which at the time made him comparable to Șincai. Ascetic, with a stern nose and eyes hollowed by candlelight reading, this intellectual had a habit: on Tuesday evenings he officiated a kind of communion ritual, especially for the city’s ladies.

It was 1792, and the banesses—daughters of great bans, wives of high officials and minor boyars—slipped through the day’s ashes, concealed in little carriages or gilded coaches, wrapped in silks, passing discreetly beneath the bishopric stairs into the small salon where the protosinghel, whose name was Iosif, began his spiritual delights.

And what confessions those women made—about their insolent sins! Things that widened his horizons and kept him informed of the city’s secret life. But whatever the subject, the central character of these confessions was always Brutaru: adored, described in details that could inflame any mind.

This captain, with broad shoulders and a cat’s gaze, was gallant and had a voice that pleased both women and men. He sent pink flowers—especially Istanbul roses—to any woman who had ended up in his sheets. And his sheets themselves were described so thoroughly that Iosif knew Brutaru detested patterned linen, always fell asleep with a scented candle by his head, adored Drăgășani wine, and above all was a lover worth sinning for—one whom even saints would not have refused, proof being that the hand of one of them had ended up with him.

Protosinghel Iosif was infected by the captain’s adventures, yet he could not stop the confessions either. Without Tuesday night, nothing made sense. No pleasure matched the intensity of those stories. So he decided he must see Brutaru with his own eyes. And, believing himself the city’s axis—as protosinghel and writer of hymns and apologues—he summoned Brutaru to appear with the bewitched hand and explain where he had got it.

At such a request, the captain laughed and slammed the door in the long nose of the messenger.

Iosif clenched his teeth and resolved to become metropolitan and drag the scoundrel in by force.

Despite every string he pulled, despite all his intelligence, his dream stopped at the rank of bishop. Still, it was not to be dismissed: immediately after the metropolitan came the Bishop of Râmnic and then the Bishop of Argeș—who was Iosif. Once enthroned, in March 1794, he wrote a letter to the prince, recounting everything I have told you so far—and more. Iosif swore the hand had been stolen from Curtea de Argeș. It was the sacred hand of Saint Filofteia, and Brutaru could be considered a thief and a profaner.

And since Alecu Moruzi sat on the throne—ready to throw himself into any conflict—he ordered, the very next day, that Brutaru be brought to the palace together with the hand.

I hardly need to tell you that this captain—let’s call him a hero—under Ottoman protection and with a beautiful voice, denied any connection to the hand. The story goes that it may still be kept today in a church in Craiova. Brutaru’s denial left Moruzi speechless.

As for Bishop Iosif, he lived through many nights in which the captain appeared in his dreams, waving the bewitched hand beneath his nose; and on the mornings after such dreams, the bishopric at Argeș filled with pink roses.