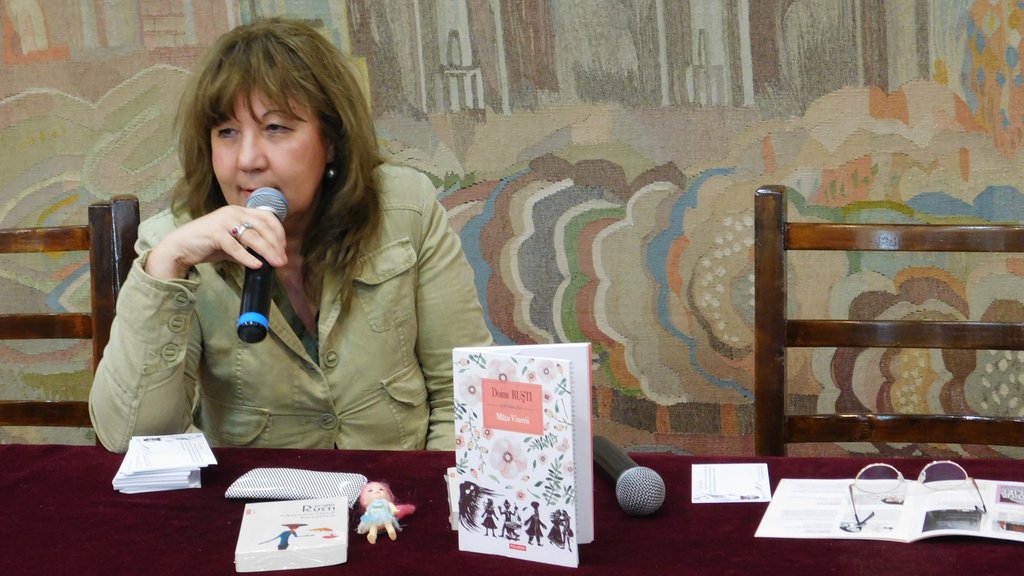

Hot News: Doina Ruști

Doina Ruști is „a writer of the first rank in today’s literature", in the words of Nicolae Breban , and „a writer of great talent and intuition”, as Norman Manea has described her, distinguished by a powerful and vibrant style.

Her novels and short stories have received major awards, been translated into several languages, and are studied in schools, enjoying wide critical recognition. Her work is marked by the blending of the fantastic with stark social realism. Her landmark novel is The Ghost in the Mill (2008), a powerful fiction about Romanian communism, included in the post-communist neo-Gothic both in J. A. Weinstock’s Routledge encyclopediaand in Studies in Gothic Fiction (Zittaw Press). Thematically complementary, Ferenike (Humanitas, 2025) is her most personal novel, a political and autobiographical fiction about memory, guilt, and feminine resistance.

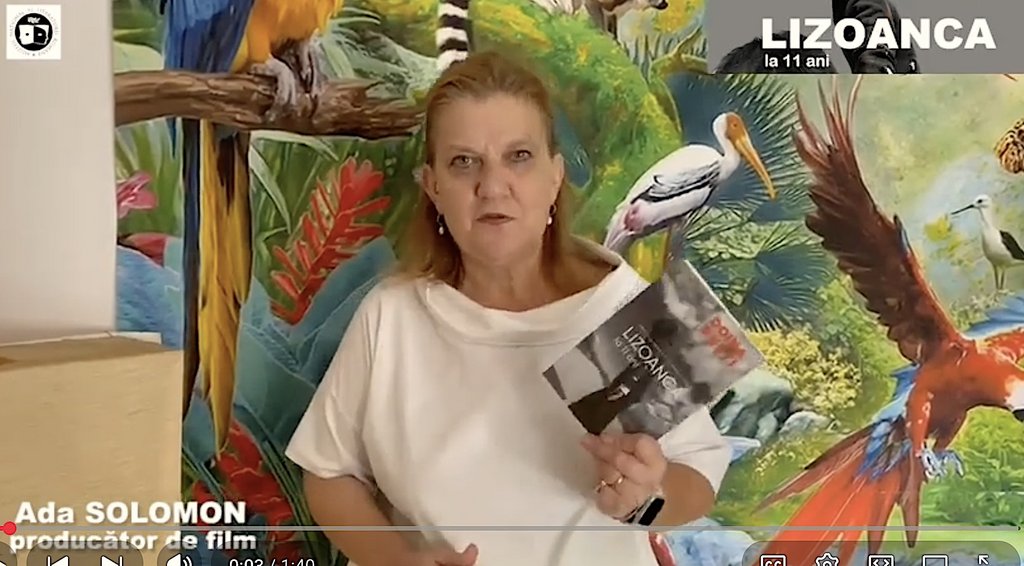

Equally acclaimed is Lizoanca at Eleven (2009), a novel about child prostitution, whose style was compared by Western critics to Camus’s The Plague (Il Libero), and which has been included in several European academic programs, among them the Doctoral School of the University of Barcelona.

The Phanariot Trilogy—The Phanariot Manuscript, The Book of Perilous Dishes (Mâța Vinerii), and Homeric—has enjoyed wide popularity. These novels explore the 18th-century Balkan imagination in an original, fabulatory mode that reinterprets history. Mircea Muthu devoted a chapter to her work in his volume Romanian Literary Balkanism. Among these, The Book of Perilous Dishes is the most widely translated, published in English in London (2022), recommended by EUFestival and featured by the Historical Novel Society.

Doina Ruști has also published ten other novels, among her recent titles Zavaidoc in the Year of Love (2024), Occult Beds (2020), and two successful YA novels (Platanos and Sălbatica).

Dan C. Mihăilescu has likened her style to that of Mircea Cărtărescu and Patrick Süskind, while Paul Cernat considers her “a novelist endowed with epic vigor and inner strength.”

Her distinctions include the Writers’ Union Prize (Bucharest Association, 2007), the Romanian Writers’ Union Prize for Prose (2008), the Ion Creangă Prize of the Romanian Academy (2009), and the Hungarian Writers’ Prize (Budapest, 2018) for Best Translated Book.

She is a university professor specializing in cultural history and world civilization.

Website: www.doinarusti.ro

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/2919952.Doina_Ru_ti

https://www.tiktok.com/@doinarusti

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/doinarusti

L’isola delle Storie, Sardinia, 2018: Roberto Merlo, Simonetta Bitasi, Doina Ruști, Omar di Monopoli and Marcello Fois

Doina Ruști / Doina Rusti

Guest on Altceva cu Adrian Artene

Interview by writer Nesrein El-Bakhshawangy, Al Majalla, Cairo

Hot News: Doina Ruști, at Cabinetul Perspektive

Born on 15 Feb 1957 in Comoșteni. With Aromanian ancestors who came from Montenegro, as well as Turkish, Jewish, and—above all—Danubian Romanian roots, Doina Ruști writes prose marked by an accentuated Balkanism and an imagination fed by diverse sources. She spent her childhood in a village in southern Romania (Comoșteni), in a family of schoolteachers who made great efforts to survive in a communist world. The absurd rules and the chaos installed at the end of the dictatorship surface fictionally in Fantoma din moară, a novel that brings forth a fabulous universe ruled by ghosts and hierophanies, and that sharply raises the question of identity in a totalitarian world—ideologically constrained and deprived of intimacy. The novel received the Romanian Writers’ Union Prize and was considered “one of the most convincing and expressive fictions about local communism published in the last decade” (Paul Cernat).

Translated into German, it received enthusiastic reviews in Neue Zürcher Zeitung:

“Doina Ruști’s book displays a wide range of literary abilities, measuring the resilience found in twentieth-century Romanian history.”

Confessions: a chat with Eugen Istodor, on Hot News (video)

In the Encyclopedia by J. A. Weinstock,

The novel The Ghost in the Mill is framed within a neo-Gothic style, opening a new direction in Eastern literature dealing with totalitarianism. The magical realism known from South American literature expands here into a form of the fantastic that metaphorizes the horrors of a closed world and of censored lives.

In the same fantastic register, with neo-Gothic accents, are other novels as well. Zogru (translated into Italian, Hungarian, Spanish, Bulgarian) creates an unusual character and a type of fantastic related to the world of Chagall’s paintings, as a daily newspaper in Santiago de Chile remarked:

“Full of humor in some sequences, in others tragic and fierce, sometimes fantastic and luminous, like a Chagall painting, what predominates in this wonderful story is the figure of the terrible loneliness in which the human spirit finds itself when deprived of love.” (Pedro Gandolfo, El Mercurio)

The story outlines the conflict through a vision placed at the boundary between fantasy and indisputable history.

Awarded the Writers’ Union Prize, the novel Zogru also benefited from a scholarship from the Hungarian government and from enthusiastic reviews.

Written in the same manner are the novels Omulețul roșu (2004), Homeric (2019), and Paturi oculte (2021), but above all Mâța Vinerii. The latter, probably her most translated novel, was praised for its imaginative world and for its style:

“Mâța Vinerii—a stylistic jubilation, a vital literature, like Süskind’s Perfume up to a point and Evgheni Vodolazkin’s Laurus from another point onward.” (Dan C. Mihăilescu). integral

The Doina Ruști’debut.

The novel Mâța Vinerii received the Hungarian Writers’ Union Prize (Budapest) for its exceptional translation, signed by Szenkovics Enikő (Budapest, 2017).

A special place is held by the novel The Phanariot Manuscript (2015), partially translated (into English, Turkish, Italian, and French) and fully translated into Albanian.

Inspired by an authentic document from the 18th century, the novel approaches a form of magical realism—fabulist and at times lyrical. The most recent edition is from 2026, Litera, in the author’s series.

“Manuscrisul fanariot is a sumptuous book, contagiously sensual. It is a poem dedicated to Phanariot Bucharest—an urb, or rather an improvised urban sprawl—rocking day and night to the languid rhythm of manele, sunk in the smoke of pipes, superstitions, rumors, and magical oriental aromas, and from time to time assaulted by endemic frenzies without object, by heavy sorrows and nameless melancholies.

If it were only that, it would still be enough.

But the story of an impossible love that shatters customs, which Doina Ruști tells us—supported by documents and with her well-known talent—lifts the curtain on a world of habits, merciless private relations, surprising behaviors, and strange habitudes that throw into perplexity even the critic with solid historical knowledge.”

The Phanariot Trilogy: The Phanariot Manuscript, The Book of Perilous Dishes, and Homeric.

Producer Ada Solomon recommends Lizoanca by Doina Ruști

Other novels adopt neo-realism. Among them, Lizoanca la 11 ani, about which the press at home and abroad wrote in superlatives, received the Romanian Academy’s “Ion Creangă” Prize in 2009.

“The trauma of Romanian society, the post-December one, is born from identity crises, from turbulence and violence with profound human implications. We thus identify a series of mature women writers—such as Ana Blandiana, Gabriela Adameșteanu, Doina Ruști, Simona Popescu, Magda Cârneci, or Herta Müller—who do not all employ autofiction, but who are adepts of the geography of memory, offering a writing of identity construction.” —

Oana Larisa Oanea, PhD thesis.

Hot News: interview with Doina Ruști about Lizoanca

The literary value of the novel was often discussed (La Opinion - Murcia, La Jornada, Mexico) as well as the truthfulness of the writing:

“Doina Ruști, with a gradually unfolding story, prolongs pain and horror to unsuspected limits, bringing causes to the surface. She managed to write about that dark and even invisible part of society, placing under question many of its essential elements. Doina Ruști has the rare capacity to capture the hypocrisy of individuals and society, violences of every kind under the most innocuous forms, and at the same time—beneath the slow epic unfolding—these violences maintain a constant erosive function. A pictorial and cinematic writing, also given by her perfect use of comparison.”

Ramón Acín, Turia, 2015.

A daily newspaper in Budapest places Lizoanca la 11 ani among the best translated books in 2015, alongside Houellebecq’s Submission, and Il Libero (Turin) compares her style to Camus’s The Plague.

Thematically continuing The Ghost in the Mill, the autobiographical novel Ferenike illustrates the experience of communism from a subjective perspective, at times with fabulatory elements. Considered a work that brings reality back into the realm of myth, the novel has been compared to The Killing of a Sacred Deer by Yorgos Lanthimos, which reactivates the tragic mechanism of punishing a hybris. (România literară).

In many of her works there is a ritual murder, a subtle reference to a sacrificial act meant to redeem history—concealed, yet constantly connected to the immediate present.

Logodnica, Mămica la două albăstrele and, in part, Fantoma din moară follow the same tendency.

With great thematic diversity, her writings address above all the erosion of the family (Lizoanca, Logodnica, Mămica la două albăstrele), psychology and women’s issues (Omulețul roșu, Fantoma din moară, Mămica la două albăstrele, Ferenike, Zavaidoc). She is often concerned with the causes of aggression. Many novels treat the theme of abortion, from the historical causes triggered by Ceaușescu’s anti-abortion decree (Ferenike, Fantoma din moară, Zogru, Ginecologii mei etc.) to the cruelties of social rules traced historically (Homeric, Manuscrisul fanariot, Zavaidocetc.).

The metamorphoses of history and the linguistic labyrinth contribute substantially to defining the Romanian space, with all its Balkan, Levantine, and Slavic influences. From the complex architecture supported by a symbolic lexicon (in Manuscrisul fanariot) to the cinematic unfoldings in Homeric, Zogru, Mâța Vinerii and the many themes in the Phanariot short stories, everything outlines a dense universe whose stories flow so naturally that they infect you, often creating models. A relevant example of this kind of imagination is Manuscrisul fanariot, a novel written in the register of a fable that incorporates, in every action, collective desires.

Bozăria was boiling. The embrace, postponed for so long, had stirred up the mud, scattering sparks and little eyes hidden under the blanket of embers. Among the tired leaves, thousands of invisible mouths let out their sighs—those small mouths, hidden in the folds of the world. Mouths that had not eaten, overtaken by a single craving. Mouths that shout, mouths that whisper for a single being. Inflamed mouths, bitten by other mouths hunted by death. Small mouths, coming out from under warmed skirts, from the hot pleats of shalvar trousers—mouths that keep alive any wretched little soul, from the louse forgotten in the filth under the nails, to the prince who lounges covered in rags. No pride of the brain is possible without the thousands of mouths of the human dream.

And these yearning mouths, born of an embrace postponed too long, invaded the city. (Manuscrisul fanariot)

And the short stories, especially the series of urban legends, preserve the same pattern.

The dominant theme of her writing, however, remains communism, understood as a system of collective degradation. Omulețul roșu (The Little Red Man)offers a symbolic, episodic image of a controlled collectivity. In Zogru, a miniature history of communism unfolds, from the proletarian assault to the commercial activism of the 1980s. The novel The Ghost in the Mill constructs a complex parable of the communist camp, while Ferenike provides a subjective vision of the same historical reality. There is hardly a novel by Doina Ruști without references to communism.

I was not interested in writing about the way ideology was used in the infernal Stalinist era, but rather in completing the picture of the complex methods through which a person, cornered by demagoguery, learns to survive. (Dialogue with Daniel Cristea-Enache)

Lizoanca at the Age of Eleven follows the mechanisms of post-communist degradation, rooted in the 1950s. Sălbatica (The Wild One)is a novel about the deportations to the Bărăgan Plain. Even in Zavaidoc in the Year of Love, the fabulous roaring 1920s are complemented by a substantial incursion into the communism of the 1960s.

Omulețul roșu received positive reviews in Romania and Italy, praised both for the originality of its expression (La Stampa) and for the complexity of its subject (Il Venerdì di Repubblica), as well as for its type of fantastic (Stato).

“…a hallucinatory, convulsive, absurd yet coherent world, as real as fantasy can be, a bizarre and unpredictable electronic Wonderland in which Laura ventures, enchanted and indomitable, like a telematic Alice.”

Roberto Merlo — “Ritorno a Babele”, Neos Edizioni, 2016, Turin

Concerned with both the fantastic register and the realistic one, Doina Ruști manages to write equally convincingly about the atrocities of the contemporary world and about lofty ideals. Her characters—whether realistic or fantastic—are memorable and striking. In her novels one often finds rapists, killers, starving people, the corrupt, and those consumed by petty ideals.

Yet with the same sure hand of a seasoned novelist, Doina Ruști also builds fantastic characters—elves, sprites, ghosts, bewitched tomcats, and wizards—which led some critics to compare her work to that of Bulgakov, Süskind, or Márquez (apud Dan C. Mihăilescu, Bojidar Kuncev).

The diverse themes, strongly anchored in the present, as well as “Doina Ruști’s rare capacity to shift narrative registers with ease, place her among the foremost writers of contemporary Romanian literature” (Nicolae Breban).

Doina Ruști, Nicolae Breban

In the novel Zavaidoc în anul iubirii (2024), she experiments with a confessional style unfolded from three perspectives, composing the love story of an interwar musician (Zavaidoc), in relation to the sensational news of the year 1923.

Carrying the confessional style further, in the novel Ferenike (2025), an overtly autobiographical writing, she builds the narration on self-projections across different periods of time—hence the impression of a branched epic built on progressive moments of action.

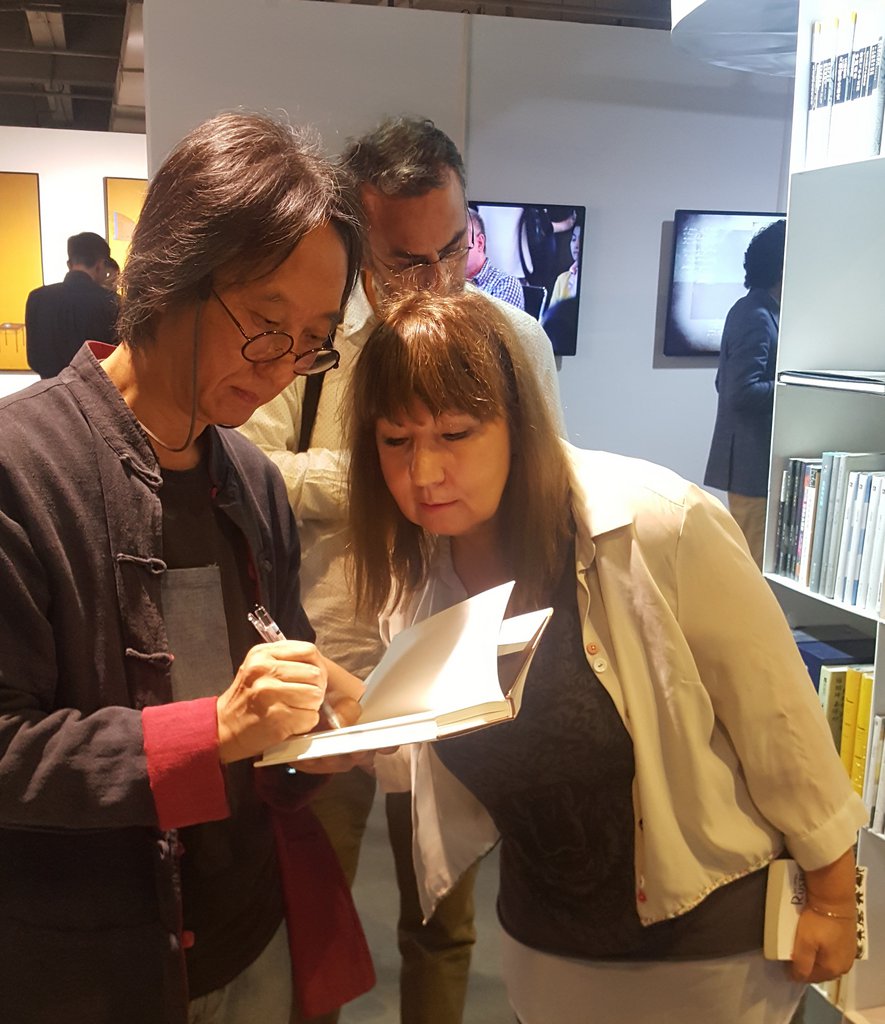

EU-China Literary Festival.

Doina Ruști lives in Bucharest and holds the academic title of university professor, specializing in the history of culture and universal civilization.

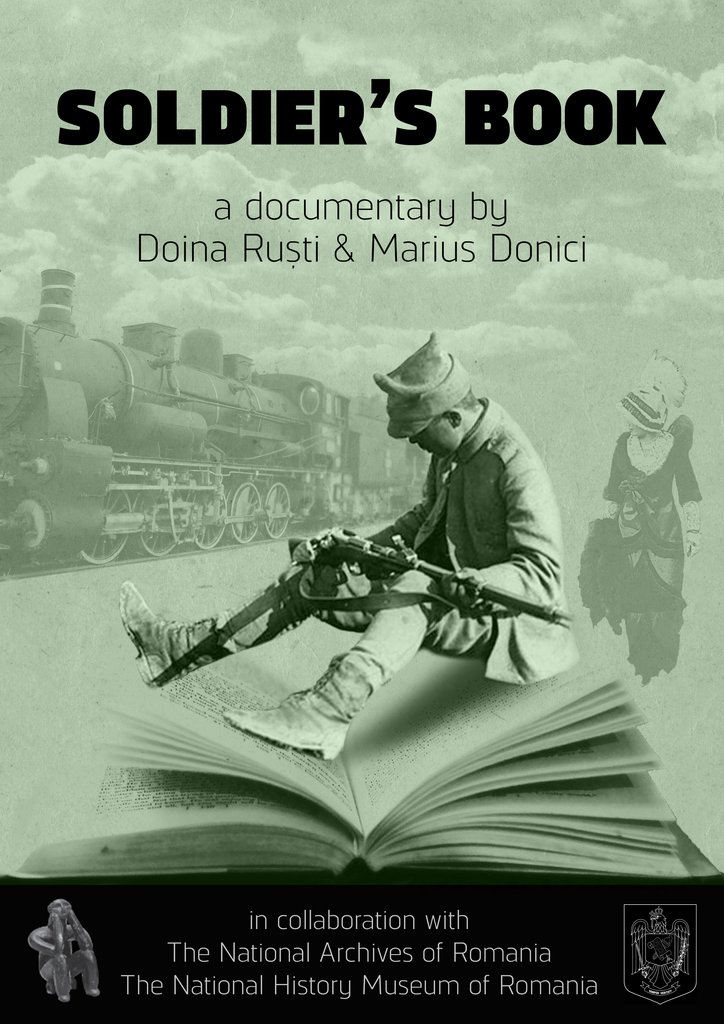

She directed a short film, based on her short story, Cristian, which premiered at Cannes in 2015.

At the National Theatre of Bucharest, with BookLand

Among other things, she initiated the magazines Ficțiunea and Cinematographic Art, and the Biblioteca de Proză Contemporană collection at Editura Litera, being involved in numerous activities: she was Director of the Media Pro Cultural Center, Dean of the Journalism Faculty at the Media University, a script specialist at Media Pro Pictures, a professor at UNATC, Universitatea Media, and the University of Bucharest, Head of Department at Hyperion University, and a member of international scientific councils and societies. She has written over 30 nonfiction books and around 50 scholarly articles, collaborating with prestigious journals, such as Umberto Eco’s Semiotica and Eighteenth Century Studies. She has served on doctoral committees and on committees for awarding academic titles, on juries for CNC, CENNAC, ICR, etc.—complementary activities, while at the center remains prose, as her principal occupation.

She signs with the pen name Ruști, convinced that giving up the name of one’s ancestors is among the great trials of a human being.

Her writings have benefited from exegetical works and academic studies, and from laudatory reviews in international newspapers and literary magazines, including El Mercurio (Santiago de Chile), Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Il Manifesto, Las Últimas Noticias, La Jornada (Mexico City), Stato Quotidiano, Turia, La Stampa, La Opinión, Il Libero, Magyar Nemzet, La Repubblica, Beijing Daily and others.

Web page: http://doinarusti.ro

(summary by Elena Costea, after the monograph signed by Pompilia Chifu: Doina Ruști, un personaj în propria carte, Casa Cărții de Știință, 2025.)

Literary networks and thematic resonances: Mircea Cărtărescu, Gabriela Adameșteanu, Herta Müller, Olga Tokarczuk, Mariana Enriquez. More

Featured guest on ALTCEVA cu Adrian Artene – Romania’s most-watched cultural podcast (2025)

The Phanariot Manuscript în Sardinia

Literary events with Doina Ruști, Mircea Cărtărescu, Gabriela Adameșteanu. Other literary meetings.

The most striking quality of Doina Ruști’s writing, visible across all her books, is the imaginative verve from which stories are woven, the inexhaustible energy from which characters and narrative threads are born. Although cast in the conventions of the historical novel, the prose D.R. writes uses historical hypotheses as pretexts to explore fantastic scenarios, intertwining fiction with metafiction in an alloy of magical realism that brings her close to the great South American masters, with whose writing many correspondences can be established. The fabulous stories in Zogru, Mâța Vinerii, Fantoma din moară or Manuscrisul fanariot are, almost every time, also stories about the writing of the story itself—subtle metanarratives about the nature of fiction, its status, and its relationship with reality. (Dumitru Mircea Buda)

https://www.doinarusti.ro/doina-rusti-dictionar-de-simboluri-din-opera-lui-mircea-eliade.html

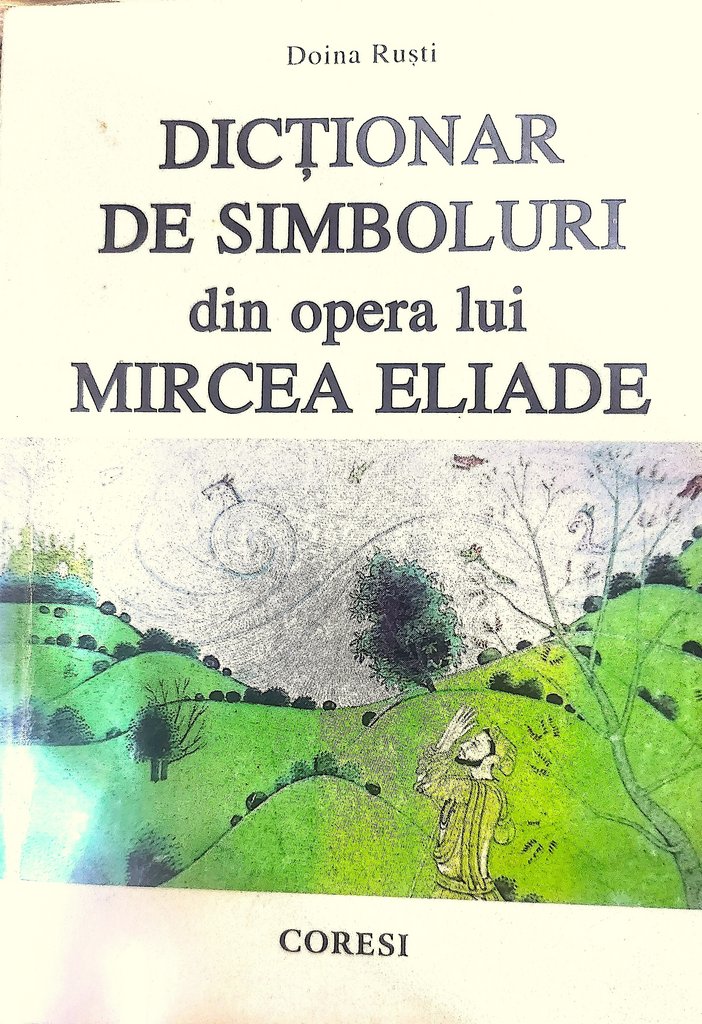

Dicționar de simboluri din opera lui Mircea Eliade appeared in 1997 at Coresi. It is the first Romanian exegesis of Eliade’s work after the fall of communism and includes both Eliade’s fiction and his scholarly work. It contains nearly 100 symbols, arranged in two major categories: 1. fundamental oppositions and 2. coincidentia oppositorum (the harmony of opposites).

This is her debut book. More.

I N T E R V I E W, Digi 24, 2025

Leipzig, 2018: Doina Ruști & Filip Florian

“What does the world hide in books? Money? Love notes? Pressed flowers?

He wrote, seduced by the watery ink, watching it dry, remembering, for a flash of a second, his teacher Poenaru’s endless ink—without letting that old memory pull him away from the military letters or from the persistent thought that his writing might die soon, wiped away by unleashed waters, or along with the paper torn to pieces by the hands of an unknown person. Of course, he wasn’t thinking about eternity, only about that victorious time when his eyes would decipher this first letter. Which meant a long, dusty road, seen with the mind’s eye like a typhoon rising from the basket of a colorless mail coach…”

Doina Ruști — Open source, novel in progress

“They could have called her Eliza, Eli, or Lizica. But it wouldn’t have suited her. Whereas Lizoanca fit like a glove: it showed her surly and hard to budge.”

Paturi oculte, Litera, 2023

Cămașa în carouri, 2023

Fantoma din moară, 2024

Mâța Vinerii, 2024

Mămica la două albăstrele, 2024

Manuscrisul fanariot, 2026

Books at Altex

Doina Ruști is an active member of the Romanian Writers’ Union, PEN Club Romania, and the Association of Fiction Creators (ACF).

She is also affiliated with Dacin-Sara and Copyro (literary rights).

She collaborates editorially with the main Romanian publishers—Humanitas, ART, Polirom, Litera,Vremea—and Bookzone, and she is involved in numerous international events.

EU–China Literary Festival, Neem Tree Press (UK), Historical Novel Society

(USA).

Among other invitations, she was a guest of the Festivalul L’Isola delle Storie – Gavoi (Sardinia, Italy), of the EU–China Festival organized by the European Union, and she had a one-month residency in Beijing.

She is a regular contributor to Ficțiunea, one of Romania’s most important literary platforms.

Her work has been presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair,

Leipziger Messe, Festival du Livre de Paris, Salone del Libro di Torino, Festivaletteratura Mantua, etc.

Paris (2023), London (2022), Belgrade (2023), Madrid (2019),

Guangzhou, Shenzhen (2018), Gavoi (2018), Santiago de Chile (2018), Istanbul (2015), Barcelona (2014), Budapest (2007, 2014, 2015, 2018, 2024), Vienna (2008), Plovdiv (2009), Torino (2009, 2011, 2012, 2013), Frankfurt (2009, 2018), (2010, 2013, 2018), Moscow (2010), Rome (2011, 2012), Granada (2011, 2019),

Düsseldorf (2013), Berlin (2013).

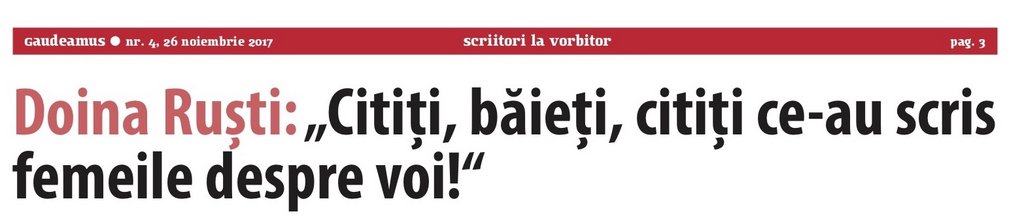

“Read, boys, what women have written about you!” — the motto of her literary dialogue.

I was kind of an explorer. I was expecting to discover amazing things, different from what my family discovered in the books they had read. My father loved poetry. My grandmother was reading contemporary novels, often Romanian ones. My mother was fond of the emotional romance books. And my grandfather’s reading taste was extremely diverse. Besides, he was the only one in the family who was reading even the newspaper. In this context, I secretly started to read Balzac at the age of 14. And not just one, but his entire volumes from our library shelf. The broad phrase and the solid structure of his novels gave me such comfort that I was convinced that I would not read any other writer for the rest of my life. Balzac was my first love or, in other words, that perfume that evaporates whenever one wants to retrieve it.

Doina Duști & her Family

Contemporary Writers, with

2007-2008 Training internship: Story editing, Script editing. Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning (WBL) & Centre for Adult Literacy and Numeracy (NRDC). Coord. John Vorhaus.

2000 Ph.D, University from Bucharest

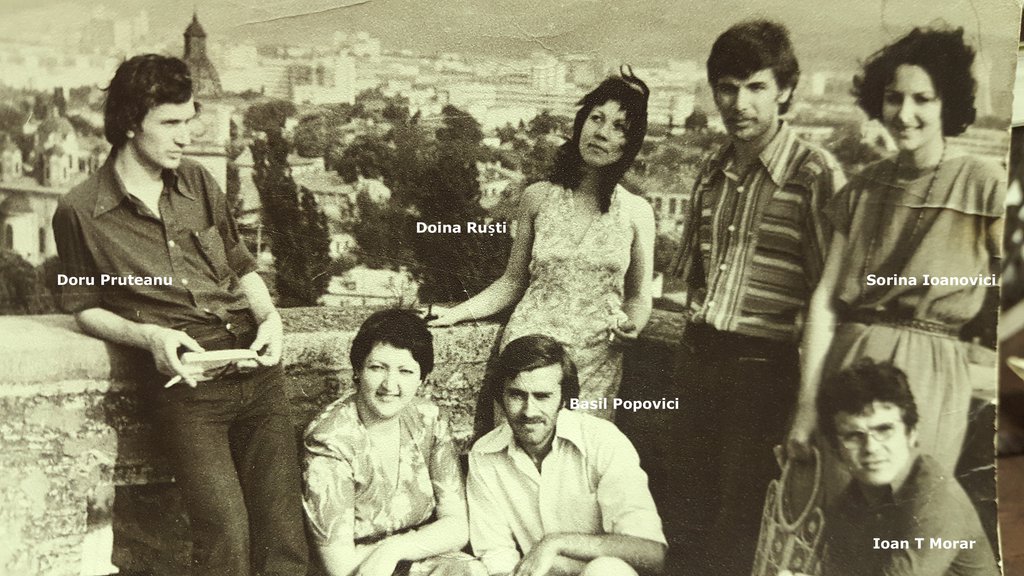

1976-1980 Faculty of Philology, "Al. I. Cuza" University, Iași

1972-1976 Garabet Ibraileanu Highschool (Classical Languages), Iași

When I graduated, I was 23 years old and i looked like a starved Asian. I was coming to Bucharest every month, carrying different manuscripts with me and trying to enter a publishing house. Usually there was someone, a janitor, and I could never get past him. Even now I have many files with short prose, that were very fashionable at the time. "The Ghost in the mill" itself dates back to the same period.

Doina Ruști, 1978, student

Bucharest University

Member of The Writers' Union of Romania

Member of PEN Club

Dacin Sara

Doina Ruști — Selected Works

An autobiographical novel based on a murder witnessed in a 1968 Danube village, weaving Balkan cultural textures with Cold War intrigue and historical-political ties involving Nixon, Ceaușescu, and Romania.

YA novel set during the Stalinist deportations, telling an optimistic love story between two teenagers. It explores resilience and hope amidst a dark chapter of history. The entire text is translated into English.

An unhappy boy, a Christmas wish, and… a metamorphosis. Platanos is a dystopia, continuing the short story of the same title, studied in middle school, written at the request of students and teachers.

The love story of a famous interwar singer, set in 1923 and told from three different perspectives. A national bestseller and nominee for Bookzone’s Best Fiction Book.

A sensual, esoteric novel set in Bucharest, blending urban realism with mysticism, erotic tension, and a spectral atmosphere. Fantasy and speculative fiction with strong appeal to YA readers.

Adapted into mini-films by 54 high schools.

The story of a magical plant, pressed between the pages of the Iliad—a fantasy-tinged mystery and love story, narrated by an enigmatic character whose identity is revealed only toward the end. The third novel in the Phanariot Trilogy.

The second volume of the Phanariot trilogy, blending magic, history, and culinary arts. Featuring sorcerers and enchanted recipes, the novel explores mystical and political intrigues of the 18th-century Balkans.

Internationally praised and translated into English, Spanish, German, Hungarian, and Chinese. Premiered in Budapest.

A Norwegian man paid me to write the story of his great love for a Romanian woman. I agreed—on one condition: I would also tell her side of the story. What emerged is a sharp, ironic bestseller about love, illusion, and the unbridgeable gulf between Eastern and Western Europe.

The first novel of the Phanariot Trilogy — an atmospheric love story set in 18th-century Bucharest, based on a real historical manuscript: an actual contract for the sale of a human being. Richly researched and layered, the novel explores themes of power, desire, and destiny in the Ottoman-influenced Balkans. It has gone through multiple Romanian editions and has been translated into Albanian, with excerpts published in English, Turkish, and Italian. A full Spanish translation is currently underway.

A powerful and controversial coming-of-age story set in rural Romania, based on a true case of an 11-year-old girl accused of causing illness in an entire village. Awarded the Romanian Academy’s Ion Creangă Prize. Translated into German, Spanish, Hungarian, Serbian, Macedonian, and Italian.

A psychological, realist novel exploring the hypocrisy surrounding child adoption and the exhaustion of the family institution, all set against the backdrop of an adulterous affair. Featuring elements of crime and deep psychological insight.

A bizarre short novel, told with a comic-strip sensibility, about a woman who seemingly accidentally kills four men, while grappling with a psychosis centered on the belief that she killed Aurelius—the beloved kitten of her grandfather.

My most important novel and greatest success to date. Upon publication, several literary magazines dedicated entire issues to it. A complex and stylistically innovative novel about Romanian communism, built around a rewritten biography told in the rhythm of a thriller, with a gothic atmosphere. It explores the idea that no crime can be judged by laws other than those that created it.

Winner of the Union of Romanian Writers’ Prose Award. Translated into German.

The story of an immortal being who lives through history from Dracula’s era to the present—a picaro who dwells in human blood and alters destinies. Also a witty and humorous dismantling of the vampire myth, exploring human solitude with irony. Winner of the Writers’ Union Prose Award. Translated into Italian, French, Spanish, Hungarian, and Bulgarian.

A fable-like fantasy and metafictional manifesto about storytelling and transformation. Set during the early years of the internet, it follows a woman’s rebellion and the uncanny appearance of a little red man—born from the frustrations of a society just emerging from communism.

„My literary debut and personal manifesto, the novel explores themes of isolation, feminine revolt, and the mutability of narrative itself."

Awarded by Convorbiri Literare magazine. Translated into Italian (two editions).

Frankfurter Buchmesse, 2017: Doina Ruști

Doina Ruști

A collection of eleven fantastical urban stories featuring time travel, miracles, love, and death—where Bucharest itself becomes a living character. The tales are subtly interconnected, culminating in a unified finale. Written in a style reminiscent of Mariana Enriquez. Several stories from this volume have been translated individually into various languages.

Around 50 short stories based on historical records and private manuscripts (lists of found, stolen, or purchased objects, etc.).

A thematic short story collection set in the 18th-century Phanariot era, exploring various acts of debauchery.

English, German, Spanish, French, Italian, Hungarian, Bulgarian, Slovenian, Macedonian, Serbian, Croatian, Turkish, Hebrew, Chinese, Danish, Russian, Albanian.

Guangzhou, 2018

Dorëshkrimi fanariot* (Manuscrisul fanariot), trans. Maniela Sota* (2024, Albanian, Prishtina).

A malom kísértete (Fantoma din moară), trans. Szenkovics Enikő. (2024, Budapest)

Zogru, Les Editions du Typhon; Marseille, 2022. Trans. Florica Courriol

The Book of Perilous Dishes, Neem Tree Press, London, 2022, 2024 (trans. James Ch. Brown)

Doina Ruști, London Book Fair, 2022

L’omino rosso, Sandro Teti, Roma, 2021 (trad Roberto Merlo)

Cong Quanshan Dao Pingyuan, trans Siqi Zhu, De Li Zan, Beijing, 2019

La gata del viernes (Mâța Vinerii), trans Enrique Nogueras, Editura Esdrújula Ediciones, Granada, 2019

Freitagskatze (trad Roland Erb), Klak, Berlin, 2018

Zogru trad. Sebastián Teillier, Descontextos Editore, Santiago de Chile, 2018

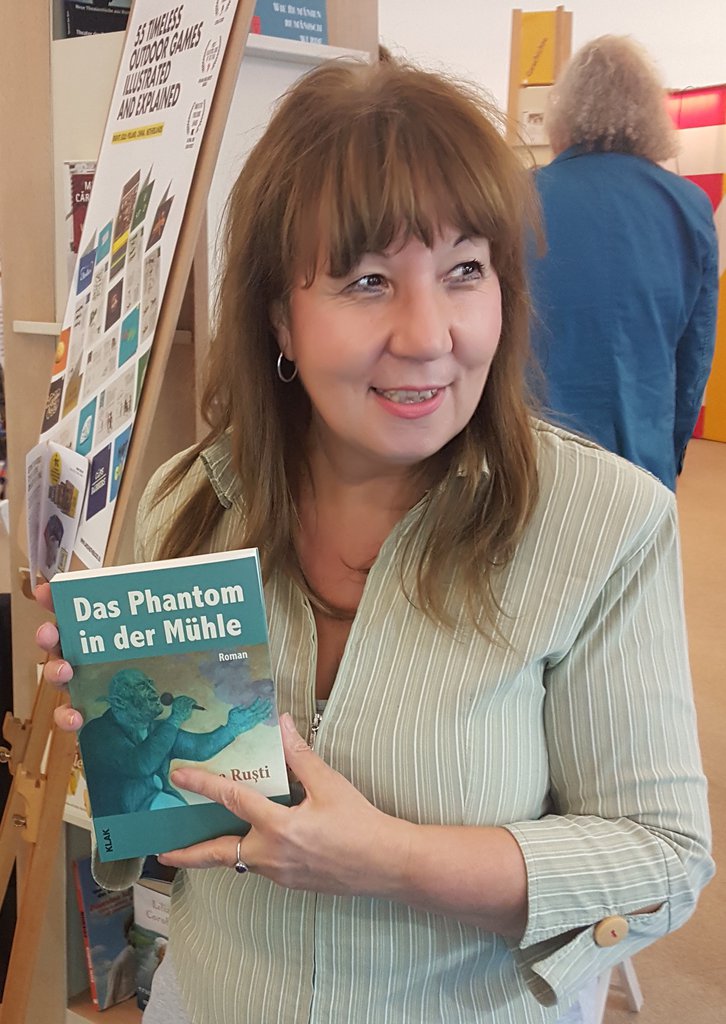

Das Phantom in der Mühle , trad. Eva Wemme, Klak Verlag, 2017, Berlin

The Truancy, The Stockholm Review Literature

The Phanariot Manuscript (trans Liana Grama), Trafika Europe, Penn State, University Libraries, nr 8, 2016

The lover (trans Andrew Davidson), Trafika Europe, Penn State, University Libraries, nr 8, 2016

Eliza (Lizoanca) trans. Alexandra Kaitozis, Antolog, 2015, Skopje

Eliza a los once años, Ediciones Traspiés, Granada, 2014 (trans Enrique Nogueras)

Lizoanca tizenegy évesen trans. Szenkovics Enikő Orpheusz Kiadó, Budapest, 2015

Fenerlilere ait elyasmasi eser (Manuscrisul fanariot), frag, trans. Leila Unal, Sözcükler , 58, aprilie, 2015, Istanbul

Zogru, Sétatér Kulturális Egyesület, 2014, prin bursa "Franyó Zoltán", oferită de guvernul maghiar (trans Szenkovics Enikő)

Lizoanca, Horlemann Verlag, Berlin, 2013 (trad Jan Cornelius)

Berlin: Jan Cornelius, Doina Ruști, Georg Aescht, Gabriela Adameșteanu.

Lisoanca, Rediviva Edizioni, Milano, 2013 (trad Ingrid Beatrice Coman)

Apartamentul 26, trans. Oana Ursulesku, Koracic, Belgrad, 2013

L’omino rosso, Nikita Editore, Firenze, 2012 (trad Roberto Merlo)

Robero Merlo, Doina Ruști, Marco Dotti, Sabian Trzan

Bill Clinton’s Hand, Bucharest Tales, New Europe Writers, 2011, (coord:A. Fincham, J. G Coon, John a’Beckett)

Kareli gomlek ve Bukreș'teki Bașka On Hadise (Cămașa în carouri și alte 10 întâmplări din București), trans. Cristina Dincer, Kalem Kultur Yaynlari, Istanbul, 2011

I miei ginecologi, in Compagne di viaggio, Sandro Teti Editore, 2011 (trad Anita Bernacchia) (coord Radu Pavel Gheo, Dan Lungu)

Ura pri univerzi, Zgodbe iz Romunije, Sodobnost International, Ljubljiana, 2011.

Zogru (trad. Roberto Merlo), Ed Bonanno, 2010, Roma; Catania

L’omino rosso (trad Roberto Merlo) în Il romanzo romeno contemporaneo, Ed. Bagatto Libri, 2010, Roma.

Roma: Stefano Petrocchi, Mircea Cărtărescu, Doina Ruști, Oana Bocșa Mălin, Horia-Roman Patapievici.

Zogru (frag.) și prezentare biobibliografică, în 11 books contemporary romanian prose, Ed. Polirom, 2006, traducere de Alistair Ian Blyth

Zogru (roman), Balkani Publishing House, Sofia, trad: Vasilka Alexova, 2008.

Învingătorul - antologia revistei Nagyvilag (trad. Noémi László), Budapesta , sept/ 2010

Cristian (trad. în fr. Linda Maria Baros), Paris, rev Le Bateau Fantôme , no. 8, 2009, ed. Mathieu Hilfiger

Cristián (trad. Sebastián Teillier), Madrid, rev. El fantasma de la glorieta, nr. 16/2008,

The begining (poem), in Under a Quicksilver Moon, 2002, SUA, Library of Congress,

Dicționar de simboluri din opera lui Mircea Eliade(frag.) în La Jornada Semanal, nr. 455; 456, 2003 (traducere: José Antonio Hernández García)

Selected film adaptations based on my fiction

– Cristian — short fiction film (writer & director).

Adapted from the short story in The Checkered Shirt.

Selections: Cannes Short Film Corner, Goa Festival, CineFest Los Angeles.

Award: Best Foreign Film – Christian International Film Festival, Florida.

– The Treacherous Shadow of a Love — short fiction film (writer & director).

Adapted from the short story of the same name.

Selections: Ascona Film Festival, Cinefest Los Angeles.

Award: Best Film – RomCon.

– Apartment 26 — short film adaptation (dir. Alexandra Băilă).

Selection: Ascona Film Festival.

– The Scam — short film adaptation (dir. Cristian Panaitescu).

Selection: Ascona Film Festival.

– Cream Truffles — feature film project in development.

Adapted from the short story.

Aici intră:

Comoara naivă

Călugărițele vrăjitoare

Dansul Soarelui

Arhivele Naționale

Miracolul de la Tekir etc.

Ateneu (literary magazine) Prize for Prose, 2015

The Romanian Academy Ion CREANGĂ Prize, 2011

The Romanian Writers' Union Prize for Best Prose/2008

The Prize of the Bucharest Writers’ Association/2007 Convorbiri literare (literary magazine) Prize for Prose, 2006

Nomination for The Book of the Year Award 2008, 2016

Diploma for supporting National Archives (ANR), 2016

The Golden Medal of "Schitul Darvari", for Literary Activity, 2008

Excellence in Teaching - National Award (2000)

"Full of humor in some sequences, in other tragic and ferocious, sometimes fantastic and luminous, like a Chagall painting, which is predominant in this wonderful story Zogru is the figure of the terrible loneliness in which lies the human spirit " (Pedro Gandolfo, El Mercurio, August 19, 2018)

"The Phantom is the narrative catalyst that makes secret forces manifest, especially those of a sexual nature, being also the most visible, single faith, dissolved in the last part of the novel." (Markus Bauer, Neue Zürcher Zeitung )

"In my opinion, the confidence, the artistry of portrayal, the exact and original description of the environment, the quest for a subtle epic crescendo, the illusion of stagnation make Doina Ruști a first class prose writer in current literature." ( Nicolae Breban, when granting the Award of Romanian Academy, 2011)

"Extraordinarias cualidades litterarias." (Antonio J. Hbero, La Opinion, 3 01 2015)

"An ironic and seductive story." (Giuseppe Ortolano - The Friday of the Republic , March 23, 2012, nr 1253)

"Amazing is the fire of a row of stunts of pungent and fulminating expressions that the author devises to describe situations and moods of her protagonist." (Alessandra Iadicicco. La Stampa , no 1815, May 12, 2012)

"Stupefacente è il fuocco di fila di trovate di espressioni pungenti e fulminanti que l'autrice escogita per descrivere situazioni e stati d'animo della sua protagonista." (Alessandra Iadicicco. La Stampa, nr 1815, 12 mai, 2012)

"The talented Romanian writer Doina Rusti, who published Lisoanca, the story of an eleven-year-old who infects an entire village with syphilis and makes victims even among her peers, is making a fool of herself, saving herself as an imaginary creature from another world . The book is also inspired by the great "health" novels, such as The Plague of Camus, where crime takes root more easily in a context of widespread disease. These are certainly the models. " (Gianluca Veneziani, Libero , May 18, 2013)

"Fa il verso ai noir fantastici la brava scrittrice rumena Doina Rusti, che ha dato alle stampe Lisoanca , storia di un’undicenne checontagia con la sua sifilide un intero villaggio, mietendo vittime anchetra le coetanee, salvopoirivelarsi una creatura immaginaria venuta da un altro mondo. Il libro si ispira anche ai grandi romanzi «sanitari», come La peste di Camus, dove il crimine attecchisce più facilmente in un contesto di malattia diffusa. questi sono certamente i modelli." (Gianluca Veneziani, Libero, 18 05, 2013)

"With her shocking book about violence against children, Doina Ruști is making a name for herself with us too. The book gets under your skin and is heavy fare. The sophisticated style contrasts with the brutal plot." (Martina Freier, ekz)

"Even the smallest detail of the novel is veridical" (Magyar Nemzet, December 31, 2015)

"A very admirable story, by the way, very well told. Highly recommended." (Miguel Baquero, The storm in a glass , December 16, 2014)

Mâța Vinerii - a stylistic jubilation, a vital literature, such as Suskind's Perfume to a point, and Evgheni Vodolazkin's Laur, from another point on. (Dan C. Mihăilescu)

The Ghost in the Mill is an imaginative novel, in line with autobiographical fiction, in which magic realism and daily realism intertwine. [...] This mill, which is an axis mundi, the center, the hearth and the obsession of the village, where the character has no clue if he has met the angel or the devil, this mill is the place where a murder occurs, as at the dawn of all worlds: a certain Max, an epileptic, is killed by mistake [...] and everybody is obliged to keep silent, thus becoming accomplices in the murder. We have all been accomplices in what has defined and punished us. This is the parable of communism. A novel with substance, a sinewy prose which, I repeat, equals a part or several parts of Mircea Cărtărescu’s Orbitor”. Dan C. Mihailescu, The man who brings the book, ProTV

"Mit ihrem erschütternden Buch über Gewalt an Kindern macht sie sich auch bei uns einen Namen. Das Buch geht unter die Haut und ist eine schwere Kost. Der anspruchsvolle Stil steht im Gegensatz zu der brutaen Handlung." (Martina Freier, ekz)

"even the smallest detail of the novel is veridical" (Magyar Nemzet, 31 decembrie 2015

"Una historia muy admirable, por cierto, muy bien narrada. Muy recomendable." (Miguel Baquero, La tormenta en un vaso, 16 12. 2014)

Shelf Media Group, Los Angeles,

Istoriile orașului, TVR, 2024

For recent media coverage, interviews, and international features, see the News & Press

For critical essays, book reviews, and scholarly studies on her work, visit Critical Reception

accesat în 2025.

Doina Ruști, author'photo

Wikipedia (EN): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doina_Ru%C8%99ti

Wikipedia (RO): https://ro.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doina_Ru%C8%99ti

VIAF: https://viaf.org/viaf/19221861

ISNI: https://isni.org/isni/0000000109584995

Library of Congress (LCCN): https://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/no00027741

Leun, this Leun threatened with becoming a kilipir, hanging from the silk sash of the boyar Dan Doicescu, looked as if he had passed through a typhoon. His hair had slipped damp from beneath his fez, the shawl had fallen over his brow, and his embroidered-sleeved vest looked like a rag.

Shyness is when a man smiles with little puppy teeth.

But the most astonishing was the shoe room, a chamber that had once been a shop with a door opening onto the street, where Lionica had gathered all the footwear that had ever passed through the house — especially shoes of every color, arranged on shelves that climbed the walls up to the ceiling. They were the former shoes of her daughters, daughters who still seemed to drift through the room, silhouettes of foam, still tethered to those many pairs: some with heels thin as stilettos, others orthopedic or military in cut; leather shoes that had struck the pavements of cities; velvet boots and ankle boots; Roman sandals with their laces coiled tightly beside them; tall boots or olive galoshes. And besides the pairs lined up on the shelves rose several heaps — beaded slippers, silk ballet flats, patent-leather shoes with buttons and buckles — hundreds of shoes that had made her stop leaving the room altogether. The windows looked out onto the garden, and beside the sill stood the bed, which at first she ignored, wholly absorbed by the footwear. She walked along the shelves, then sat down on the floor. It was a room with old wooden planks, once painted green, now faded in places from years of scrubbing; the bleached patches made it look like a medieval map.

At a table by the window sat Rufă himself. His hair was carefully combed back over his head, and he was dressed in a beige suit, glossy and soft, in total discord with the entire room, crowded with tables covered in crumpled cloths, scorched here and there by cigarettes.

The hunted man acquires a blind faith in destiny, scattered and transformed over time into a true corpus of geographically rooted superstitions.

Clouds drifted above the Dâmbovița, and in the distance the Bozărie was stirring. Leun opened the window. From the river’s mud rose to his nostrils the smell of the city, and from among the elder bushes small mouths called him by name.

Leun was his hidden name, which only Tranca’s serpent tongue had known how to uncover.

The gambler needs spectators. He wants recognition, glory, applause.

Zogru generally disliked the idea of slipping into a man with whom a woman was already in love, for it deprived him even of that small pleasure of being the conqueror himself.

The wolf can be beaten and killed, but no one will take his freedom. He leaves his steps in the snow, and even if bloodstains remain behind him, he goes on dreaming of his endless forest.

Kilipir measured the very scale of failure. It was not merely the dagger hurled into the middle of the forehead, but a red-hot nail, a drill made to crush, over time, with the slowest motion, the flesh of a man condemned to lose, one by one, his house, his name, and his faith.

Through someone’s dream a cat will pass, dissolved in the vapors of evening, and that dreamer of cats will be my first reader.

Love is the happiness of being nothing more than a rag rotting in a stranger’s wound.

When I heard him mentioning my mother, whom he had started bespattering in something resembling the English language, calling her “a Norwegian whore”, I opened the door and headbutted him without the slightest hesitation. I yelled at the top of my lungs too, so that bitch, Julia, could hear me loud and clear: “I’m an Irish man, you fucking asshole, I’m from Belfast, we would stick some Semtex up your ass" trailer

You must caress the roast, speak to the soup, sweets need coaxing like a child, and the cold cuts must be adorned and fussed over like a bride.

The word gypsy descends from the name Goiu Lizate Tyaga, the vagabond for whose mad dream his descendants preserved not the slightest trace of respect.

Freedom is nothing but the tear that burrows into flesh.

Three is the number of hypocrisy. It destroys the pair. It gives the illusion of perspective.

In the light of Istanbul, made of moon and stars, the Greek and the Macedonian woman became a single being. They opened their souls, shared their small sins. Together they tasted the sweetness each had been saving for another.

Despite its reputation as a cheerful place, Bucharest is full of sighs.

In the history of the Romanians there is only one reason for pride: Bucharest, this city whose name sounds like a pack of dogs.

The name of Bucharest is made of apricot blossoms and the heat of peppers roasted on charcoal.

The desired woman is like opium that sets your mouth on fire, like grief that makes you crumple at sunset.

Du-te-n pizda mă-tii (Return to the place you were before birth.) is an act of goodwill, a finger raised at the right moment, a warning, help offered in need, even a polite dissociation from someone who has lost his way. It says briefly what a long speech about weaknesses would have said. You made a mistake! That’s that! But you can start again! Let’s pretend it didn’t happen! You are new, unborn, erased from history.

On an August day in the year 1481, the ghost vanished as it had come, closing itself inside a green bud, soon lost among the other souls that keep the world alive.

Most often grave things happen not because the master does not know the story, but because he has not heard it properly.

A sheet of paper written by a human hand is often merely the consequence of events left in shadow. And among the many deeds hidden in the script of our manuscript lies a certain morning in Manda’s life, without which the day of the manuscript would have no value.

The past is like a dog that keeps tearing at your hem without pause, while the present is a mongrel that tricks you into holding it in your arms, making you forget the future — an Afghan hound.

If you believe me, I can still taste betrayal the same way now — like an evening breath in which the scent of coffee mingles with the metallic rustle of an arnaut’s uniform.

“If you need to clear the air with these gentlemen, better remove yourself from the car!” Julia’s boyfriend, or whatever he was, didn’t seem like much. I had fought more fearsome men in my life.

I was taking small steps along the former Elisabeta Boulevard, from which today not even the name remains, and when I reached the spot near the Carpați restaurant — where there is now a bookshop — Zavaidoc was walking just ahead of me, no more than two meters away. He was smiling and serene, without the sadness that followed Matilda. He was coming toward me warmly, smiling as he once did.

You don’t waste time on a generous man. You don’t linger over drinks. You don’t philosophize about his gesture. Nor do you add him to your list of friends. He remains only a guarantor — the man with the money.

I felt alone, and the strange thing was that I longed most for Platanos, whom I had thought I would discover quickly, given how tall he was. And then I remembered the library, the Striped Notebook, and his father, the bearded librarian. Only then did I realize I did not even know his name. Whom was I supposed to ask? Still, I set off toward the library. Perhaps they had another position as a doorman for me. I asked left and right how I might get there. Few had heard of the library, and it took me some time to find it: a gigantic building that seemed made of glass, obviously without a roof. The books were protected, in special rooms, beneath tarpaulins or awnings, but the few readers leafed through them in a wide enclosure, stiff and upright, standing beside what had once been a window, now without panes — a torn mouth, a breach besieged by plants.

Everything that followed — the salads, the garnishes, and the other companions of the roast — turned into love letters, bouquets of flowers, and serenades through which men send their desires and news of the pulse of their blood. Only Silică was not thinking of women.

This name stirred through every nook and cranny, like a breeze, like a rustle, like a collective sigh. In his blood, this name had bred offspring.

There are people ready to enter life early, for whom school is a reckless waste of time. Schools ought to turn into clubs, serving strictly as spaces for socialization.

Lizoanca at the age of eleven (Lizoanca la 11 ani)

The Ghost in the Mill (Fantoma din moară)

Zogru

The Phanariot Manuscript (Manuscrisul fanariot)

The Phanariot Manuscript (Manuscrisul fanariot)

The Ghost in the Mill (Fantoma din moară)

The Little Red Man (Omulețul roșu)

The Little Red Man (Omulețul roșu)

Compiled by Pompilia Chifu

A selection of studies, articles, and academic works dedicated to Doina Ruști’s writing, published in journals, collective volumes, and international databases (over 200 critical studies).

See also: Critical Reception

Dan C. Mihăilescu – Woman with a Little Man, in Romanian Literature in the Post-Ceaușescu Era, II. The Present as Dehumanization, Polirom, 2006

Dan C. Mihăilescu – Romanian Literature in the Post-Ceaușescu Era. II. Prose, chapter “Apocalyptic Realism and Derision,” Polirom, 2006

Roberto Merlo, Quaderni di studi.., no. 5, 2010, Edizioni dell’Orso, Turin

Mircea Muthu - cap. The Phanariot Manuscript (Manuscrisul fanariot), în Balcanismul românesc, Școala Ardeleană, 2017, p. 713.

Alina Bako - Cartografii ficționale. Perspective asupra prozei românești, Casa Cărții de știință, 2025

Catrinel Popa - Trecutul ca poveste, Pro Universitaria, 2021.Geo Vasile – The Elixir of Narrative, in The Novel or Life. European Prose Writers, MNLR, 2007

Dumitru Augustin Doman – The Avatars of a Spirit, in The Novel Reader, Ed. Pământul, 2010

Emanuela Ilie – The Fantastic and Alterity, Junimea, 2013

Roberto Merlo – Zogru by Doina Ruști, Between History and Myth, in Quaderni di Studi Italiani e Romeni, 5, 2010, Edizioni dell’Orso, pp. 121–136

George Marcu – Contemporary Female Personalities from Romania, Meronia, 2013

Andrei Simuț – The Post-Communist Romanian Novel…, EMLR, 2015

Roberto Merlo – “Return to Babel,” Neos Edizioni, Turin, 2016

Călin Teutișan – “Levantine Fantastic,” in Encyclopedia of Imaginaries in Romania, ed. Corin Braga, Polirom, 2020

Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock – The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters, Routledge, 2014

Elena Crașovan – The World of the Living Dead…, Dacoromania Litteraria, 2017

Tania Radu – Risky Games, in Literary Fanzines, Humanitas, 2014

Catrinel Popa – The Fantastic Revisited in East-Central European Contemporary Fiction, 2019

Raluca Andreescu, in Studies in Gothic Fiction, Zittaw Press, 2011

Adriana Răducanu – Confessions from the Dead: Reading Ismail Kadare’s Spiritus as a ‘Post-Communist Gothic’ Novel, in Postcolonial Europe? Essays on Post-Communist Literatures and Cultures, eds. Dobrota Pucherova and Robert Gafrik, Brill, 2015

Alina Bako – Images of Alterity in Contemporary Women’s Prose, Speculum, 2017

Dana Bădulescu, Maria-Sabina Draga Alexandru and Florina Năstase (eds.) – Women’s Imaginary Cooking and Appetites Across Cultures: Studies in Literature, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2025

Pompilia Chifu – Doina Ruști, a Character in Her Own Book, Casa Cărții de Știință, 2025 (monographic study)

Christene d’Anca – Mediating a Loss of History…, Journal of European Studies, 2018, Sage Journals.

Dana Sala – Alessandro Baricco’s Seta and Doina Ruști’s Manuscrisul fanariot, 2015

Alina Puskás-Bajkó – Maiorca or on the gipsy magic realism…, Journal of Romanian Literary Studies, 2021

Florina Cotoară – Zogru – the Initiating Journey, JRLS, 2017

Dumitru-Mircea Buda – Homeric or about the magical powers of storytelling, Acta Marisiensis, 2019 Integral

Cristina Balinte – The memory crisis…, Philology & Cultural Studies, 2017

Ilona Bădescu – Comparative structures referring to the human body in Doina Ruști’s Manuscrisul fanariot, Analele Universității din Craiova, Lingvistică, no. 1–2, 2022, pp. 237–253. CEEOL

Inga Duță – Expressive oppositions in Ciudățenii amoroase…, 2024

Simona Antofi – Gastronomy and literature in Doina Ruști’s novel Mâța Vinerii, Analele Universității Ștefan cel Mare, Suceava

Alina Bako – Contemporary Romanian Historical Fiction…, 2025

Valeska Bopp-Filimonov – Saddening Encounters. Children and Animals in Romanian Fiction and Beyond, Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai, 67/2022

Raluca Andreescu – A Pilgrim Through Mortal Blood: A Post-Communist Rewriting of the Western Vampire, ResearchGate, 2011

Gabriela Chiciudean- Lizoanca, wounds and cruel reality, Swedish Journal of Romanian Studies, vol 8, nr 2, 2025

Carmen Adriana Gheorghe - The Book and the Separate Room, Trivent, 2025

Simona ANTOFI, Despre magie și eros în actualitate – Doina Ruști, Homeric, ,,Comunicare interculturală și literatură” – ,,Communication interculturelle et littérature”, 2019, vol. 26, nr.1

Amalia Drăgulănescu - Fascination and Aversion* – the Imaginary of the Phanar at Three Romanian Writers*, [Studii și cercetări științifice. Seria filologie, 53/2025]

Emanuela Ilie - Lizoancala la 11 ani. Copilărie devastată, sexualitate și abuz, Annales Universitatis Apulensis. Series Philologica, No. 25/1/2024

***Doina Rusti. Lumi, istorii, combinații simbolice , volum omagial de studii, coord. Emanuela Ilie, Vasiliana, 2022

Adrian Jicu – “The Phanariot Manuscript – a fabulous novel”, Ateneu, no. 10, October 2015

Valeria Manta Taicuțu – “The Phanariot Manuscript”, Cafeneaua literară, December 2015

Călina Bora – “The Phanariot Manuscript”, Steaua, no. 7–8, 2015

Magdalena Popa Buluc – “The Phanariot Manuscript”, Cotidianul, April 7, 2015

Tudorel Urian – “The Mysteries and Charm of Bucharest (The Phanariot Manuscript)”, Viața Românească, no. 11, November 2015, p. 8

Ioan Groșan – “A revelation-novel”, Observator cultural, no. 792, October 2, 2015

Mihaela Grădinaru – “Prisoners inside the manuscript”, Cronica veche, no. 10, October 2015

Dan Cristea – “A poematic version of the historical novel”, Luceafărul de dimineață, no. 7, July 2015, p. 4

Mariana Criș – “The Phanariot Manuscript”, Cultura, no. 525, July 18, 2015

Stelian Țurlea – “Simplicity opens the path to grandeur: Doina Ruști’s The Phanariot Manuscript”, Ziarul financiar, May 21, 2015

Adrian G. Romilă – “Phanariot décor”, Convorbiri literare, May 2015

Lucian Alecsa – “The Phanariot Manuscript”, Hyperion, no. 4–5–6, 2015

Cristian Teodorescu – “The Phanariot Manuscript”, Cațavencii, April 16, 2015

Alina Purcaru – “Idylls from Phanariot Bucharest”, Observator cultural, no. 770, May 1, 2015

Gabriela Gheorghișor – “The magic of storytelling”, Ramuri, no. 4, 2015

Luminița Corneanu – “Love in Phanariot Bucharest”, România literară, April 3, 2015

Emanuela Ilie – “The Phanariot Manuscript”, Convorbiri literare, March 2016

Mircea Muthu – “The Phanariot Manuscript. Word, style”, Apostrof, no. 4 (311), April 2016 (link in list)

Gabriel Enache – “The Phanariot Manuscript”, Cultura de sâmbătă, March 3, 2016

Dana Sala – “Alessandro Baricco’s Seta (Silk) and Doina Ruști’s* Manuscrisul fanariot* (The Phanariot Manuscript)**”, in Weaving a Narrative from Metamorphoses, 2015, ALLRO, vol. 22, article code 487-121

Alina Puskás-Bajkó – “Maiorca or on the gipsy magic realism of seduction in Doina Ruști’s Manuscrisul fanariot**”, Journal of Romanian Literary Studies, no. 6/2021, p. 546

Ilona Bădescu – “Comparative structures referring to the human body in Doina Ruști’s Manuscrisul fanariot**”, Analele Universității din Craiova, Lingvistică, no. 1–2, 2022, pp. 237–253 (CEEOL)

Claudia Nițu – The struggle for identity and freedom in Manuscrisul fanariot, Elefantul de bibliotecă

Bianca Burța Cernat – “Fiction and magic in Phanariot Bucharest”, Observator cultural, no. 863, 2017

Gabriela Gheorghișor – “Phanariot Bucharest from enchanted coral”, Ramuri, no. 4, 2015 (link in list)

Alina Bako – “Contemporary Romanian Historical Fiction as a Mediating Transistor of the ‘Zemiperiphery’ (The Phanariot Manuscript)”, Studia Universitatis, Philologia, 2025, vol. 70

Inga Druță – “Expressive oppositions in ‘Ciudățenii amoroase din Bucureștiul fanariot’”, in Limbă, Literatură, Folclor (article; IDS/IBN link in list)

Amalia Drăgulănescu - Aspects of the New Romanian Magical Realism in the Novel Homeric by Doina Ruști , „Journal of Romanian Literary Studies” - International Romanian Humanities Journal, Arhipelag XXI Press, Târgu-Mureș, 2025

Inga Duță – “Expressive oppositions in Ciudățenii amoroase…**”, Cercetări lingvistice, 1, 04.2024 (Institute of Philology “B.P.-Hasdeu” of MSU). https://ibn.idsi.md/ro/vizualizare_articol/207030

Christene d’Anca – “Mediating a loss of history in Doina Rusti’s The Ghost in the Mill**”, Journal of European Studies, vol. 48, 3–4 (2018), pp. 265–277; first published Oct 22, 2018

Andrei Simuț – “Fictionalizing panoramas of the communist past: Un singur cer deasupra lor, Fantoma din moară, Pupa russa”, in The Post-Communist Romanian Novel…, EMLR, 2015

Doris Mironescu – “Fantoma din moară”, Suplimentul de cultură, May 9–15, 2009, p. 10

Constantin Dram – “The novel’s multiple memory”, Convorbiri literare, no. 10, October 2008

Mihaela Ursa – “History at MAX”, Apostrof, no. 11, 2008

Adrian Neculau – “The mill, the ghosts, the fear”, Ziarul de Iași, April 27, 2009

Adriana Bittel – “Doina Ruști: Fantoma din moară**”, Formula AS, no. 854, 21.02.2009

Radu Nedelcuț – “Look back in anger”, Noua literatură, April 2009

Silviu Gongonea – “Fantoma din moară”, Mozaicul, no. 7/2009

Ovidiu Șimonca – “Without pathos…”, Observator cultural, no. 465, 2009

Dan Cristea – “In seeking the origins”, Luceafărul, no. 1, 2009

Mihai Iovănel – “Travelling circular”, Cultura, no. 4, 29.01.2009

Bianca Burța Cernat – “Rehabilitating the realist illusion”, Observator cultural, no. 459, 29.01.2009

Șerban Axinte – “Memory and suspense”, Observator cultural, no. 459, 29.01.2009

Paul Cernat – “Romanian communism in the mill of magical realism”, Revista 22, “Bucharest Cultural”, no. 2, December 2008

Adriana Stan – “Fantoma din moară”, Cultura, 29.01.2009

Lucian Alexa – “Fantoma din moară”, Evenimentul zilei, September 26, 2009

Constantin Dram – “Reality in struggle with fiction”, Convorbiri literare, April 2008

Horia Gârbea – “Editorial event: Fantoma din moară**”, Săptămâna financiară, 03.10.2008; and Luceafărul, no. 32/2008

Markus Bauer – “International aktuelle themen… [Fantoma din moară]”, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 04.01.2018

Elena Crașovan – “The World of The Living Dead…”, Dacoromania Litteraria, IV/2017, pp. 93–109

Bianca Burța Cernat – „Banalitatea Răului”, Revista 22 („Bucureștiul cultural”), 6 octombrie 2009.

Paul Cernat – „Valachia News”, Revista 22 („Bucureștiul cultural”), 3 noiembrie 2009.

Gabriela Gheorghișor – „Spectrul memoriei”, Dilemateca, nr. 31, decembrie 2008.

Gabriel Coșoveanu – „Mesaje spectrale”, Ramuri, nr. 10, octombrie 2008.

Luminița Marcu – „Doina Ruști, pe fîșia îngustă… Parodierea vampirismului”, Suplimentul de cultură, 29 aprilie–5 mai 2006.

Gelu Ionescu – Târziu de departe, Cartea Românească, 2012 (pp. 112 și urm.).

Florin Irimia – „Un aer de sfârșit plutea peste lume”, Suplimentul de cultură, nr. 392, 23 martie 2013.

Monica Grosu – „Privirea din obiectiv”, Luceafărul de dimineață, nr. 11–12, noiembrie–decembrie 2013.

Mircea Pricajan – „From Here to Eternity”, Familia, iunie 2013.

Andreea Banciu – „Mămica la două albăstrele – despre dificultatea de a fi cititor detașat”, Semne bune, 25 decembrie 2013.

Tudorel Urian – „Mămica la două albăstrele”, Viața Românească, nr. 7–8, 16 octombrie 2013.

Tania Radu – „O ficțiune fericită”, Revista 22, 20.10.2015.

Mihai Diac – „Un nou roman de avangardă al scriitoarei Doina Ruști”, România liberă, 29.09.2019 (link în listă).

Luiza Negură – „Liber Historiarum”, Convorbiri literare, noiembrie 2025.

Elvira Sorohan – „Un roman despre vremea poeților Văcărești”, Convorbiri literare, august 2015.

Ileana Marin, Ferenike, Ficțiunea, 113

Ramón Acín – „Eliza a los once años. Doina Ruști”, în Turia, nr. 115, Instituto de Estudios Turolenses, 2015, p. 323.

Markus Bauer – „International aktuelle themen… [Fantoma din moară]”, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 04.01.2018.

Pedro Gandolfo – „Un espíritu ligeramente inquieto (Zogru)”, El Mercurio (Chile), 19 august 2018.

Leonardo Sanhueza – „Llega a Chile un espíritu mortífero…”, Las Últimas Noticias (Santiago), 7 mai 2018.

Dulce Carpio – „Travesías y entretenimiento por una niña”, La Jornada (Mexico City) (link Issuu în listă).

Marco Dotti – „Zogru”, Il Manifesto (Italia), 15 mai 2011.

Alessandra Iadicicco – „L’omino rosso”, La Stampa, nr. 1815, 12 mai 2012.

Giuseppe Ortolano – „Com’è strano l’amore a Bucarest a quarant’anni”, Il Venerdì di Repubblica, 23 martie 2012.

Gianluca Veneziani – „Gli allegri assassini venuti dall’Est…”, Il Libero Quotidiano (Torino), 18.05.2012.

Roberto Merlo – Ritorno a Babele, Neos Edizioni, Torino, 2016.

***– „Laura, l’omino rosso e le mille vie del web”, Il Citattido, 16 agosto 2012.

Antonio J. Ubero – „Las fábricas del odio”, La Opinión, 03.01.2015, p. 5.

Eftenie, Anca Luminița – Hibridizări ale fantasticului. Mircea Eliade și Doina Ruști, coord. lect. univ. dr. habil. Florinel I. Oprescu, Universitatea de Vest din Timișoara (rezumat; link UVT în listă).

Costianu, Georgeta Pompilia – Particularități tematice, construcție textuală și profil identitar în proza Doinei Ruști, cond. șt. Nicoleta Ifrim, Universitatea „Dunărea de Jos” din Galați, 2022 (link ARTHRA/UGAL în listă).

Parchirie, Andrada-Giorgiana – Ipostaze ale fantasticului în proza românească postbelică, coord. prof. univ. dr. Dorin Ștefănescu, UMFST „George Emil Palade” Târgu Mureș (rezumat; link UMFST în listă).

Oanea, Oana-Larisa – Metamorfoze ale experienței comuniste în discursul epic feminin postdecembrist/ Metamorphoses of the Communist Experience…, coord. prof. univ. Rodica Ilie, Universitatea Transilvania din Brașov (rezumat; link UnitBV în listă).

Adina Mocanu – Female body in the Postcommunism Romanianhttps://www.euromedwomen.foundation/pg/en/profile/adinamocanuliterature and she is interested in themes such as sexuality, vulnerability, illness and violence. (despre Lizoanca la 11 ani):\

AnamariaLaura Ciocan - TIPOLOGII FEMININE ÎN PROZAROMÂNEASCĂ A ANILOR 2000, TG. Mureș, coord. Iulian Boldea, 2023.

See also: CRITICAL RECEPTION of the novels signed by Doina Ruști

2.1. Novels

Platanos, Youngart, 2025

Sălbatica, Booklet, 2025

Ferenike, Humanitas, 2025

Zavaidoc în anul iubirii, Bookzone, 2024

Paturi oculte/Occult Beds, Litera, BPC, 2020

Homeric, Polirom, Fiction Ltd, 2019

Logodnica, Polirom, Fiction Ltd, 2017

Mâța Vinerii/The Book of Perilous Dishes, Polirom, Fiction Ltd, 2017, Top 10+, 2018

Manuscrisul fanariot/The Phanariot Manuscript, Polirom, Fiction Ltd, Top 10+, 2016, 2017

Mămica la două albăstrele, Polirom, 2013

Patru bărbați plus Aurelius /Four Men plus Aurelius, Polirom, 2011

Cămașa în carouri și alte 10 întâmplări din București /The Plaid Shirt (epic puzzle), Polirom, 2010, Litera, 2023

Lizoanca la 11 ani (novel), Ed. Trei, 2009; Polirom, 2017; Litera 2022

Fantoma din moară/The Ghost in the Mill, Polirom, Ego. Proză, Litera: 2008; 2017, 2024

Zogru (novel), Polirom, Iași, 2006; 2013

Omulețul roșu/The Little Red Man, Ed. Vremea, Bucharest, 2004; 2012

2.2. Short fiction

2.2.1. Volumes

Depravatul din Gorgani, Litera, 2023

Ciudățenii amoroase din Bucureștiul Fanariot/The Curious Loves of Phanariot Bucharest, Litera, 2022

2.2.2. Periodicals, anthologies, textbooks

The Blue Forest, textbook, 7th grade, Geanina Oprea

Cocrișel, in When the Future Was Small (ed. Florentina Sâmihăian), foreword by Liviu Papadima, illustrations by Oana Ispir & Dan Ungureanu; ART, Arthur, 2021

Herr, in Thirteen, Litera, BPC, 2021

Platanos, textbook for 8th grade, ART Publishing House, 2020

The Secret, “Echinox Anthology”, no. 1, 2018

Kant and Max, in the anthology “PEN95 Romania”, 2017

The Treacherous Shadow of a Love, Apostrof magazine, no. 8, 2016

European Union, in the volume How We Love, Vellant Publishing House, 2016

The Lost Militiaman, in the volume Writers at the Police, Polirom, 2016

Cream Truffles, România literară, no. 31, 2015

The Mangy Forest, Ramuri, no. 2, 2014

35 Minutes After, România literară, 2014

The Visit, România literară, no. 8, 2013

The Black Fiat, Viața românească, no. 9–10, 2013

Prince Avolo, in Who’s Afraid of Computers? (eds. Tina Sâmihăian, Liviu Papadima), Arthur Publishing House, 2013

Trattoria Amore, Catchy, April 30, 2012

The Mall Cinema, România literară, no. 7, 2012

The DNA Crypts, Ziarul financiar, June 15, 2012

The Lover, România literară, no. 29, 2011

How Cici Bezergheanu’s Disenchantment Began, Bucharest Cultural, no. 107, July 19, 2011

Provincial Magazine, Obiectiv Cultural, May 2, 2011

The Red Whistle, Timpul magazine, March 2011

Apartment 26, Timpul, March 2011

Lost Details, in “Contemporary Romanian Literature”, Echinox anthology, 2011

Topaz Earrings, “Old and New Bucharest”, Editura Subiectiv, 2011 (ed. Andrei Slăvuțeanu)

Năltărogul, “Old and New Bucharest”, Editura Subiectiv, 2011 (ed. Andrei Slăvuțeanu)

Mrs. Glodeanu’s Long-Awaited Hour — Revista 22, “Bucharest Cultural”, no. 103, 2010

The Devil in Love, Revista la plic, no. 4, 2010, Chișinău

Bill Clinton’s Hand, Revista 22, “Bucharest Cultural”, no. 95, 2010

The Message in the Bottle, “Mnemosyning”, “Triade”, 2010

My Gynecologists, in the volume “Travel Companions” (eds. Dan Lungu, Radu Pavel Gheo), Polirom, 2010

A Murderous Lout’s Noon, România literară, no. 25, 2010

The Imp from Batiște Street, Luceafărul de dimineață, no. 1–2, 2010

Beyond the Purple Gate, in What’s the Deal with Reading, Art Publishing House, 2010 (eds. Liviu Papadima, Tina Sâmihăian)

The Victor, Convorbiri literare, March 2009

Marțisara’s Gift, in Bookătăria de texte (“The Text Kitchen”), “The Illustrators’ Club” (ed. Florin Bican), 2009 (collective volume)

The Wig Shop, România literară, no. 52, 2009

An Easter Story, România literară, no. 15, 2009

The MP Collapses, “Nine Unpublished Political Novellas”, Tritonic Publishing House, 2009 (editor/coordinator: Horia Gârbea)

Horia Gârbea (collective volume)

A Crime and Four People Who Chatter On, Hyperion magazine, 1–3, 2009 (story written in 1990)

The Padlock and the Key, România literară, no. 45, 2008

SIGCHLD, fork() and sleep(), under the title The History Lesson, România literară, no. 29, July 25, 2008

Cherries in Asphalt, in “Pranks, Tears, and a Bucket of Blood”, Limes Publishing House, 2008 (ed. Mircea Petean) — Writers’ Union anthology

My Uncle, the Postman, Mozaicul, no. 4, 2008

European Union, România literară, no. 48, 2007

Cristian, România literară, no. 17/2007

Tits, in “Romanian Erotic Stories”, Editura Trei, 2007

Near St. Silvestru Church, Convorbiri literare, November 2006

Lulu, Vatra, no. 11–12, 2005

The Message, Viața Românească, no. 8–9, 2004

F A I R Y T A L E S

The Beauty from Milk, The Red Man, etc., in Romanian Mystical Fairy Tales and Stories, Retold (in collaboration with Horia Gârbea and Liviu Ioan Stoiciu), Paralela 45 Publishing House, 2007

The Imp’s Dream, in the volume More and More, Art Publishing House, 2017, etc.

3. Editions, texts published in other languages (selective)

3.1 Novels – in translation

A malom kísértete, Orpheusz Kiadó, Budapest, 2024. Trans. Enikő Szenkovics

Zogru, Les Editions du Typhon; Marseille, 2022. Trans. Florica Courriol

Doreshrimi fanariot, Dukagjini Publishing House, trans. Maniela Sota, Prishtina, Republic of Kosovo, 2024

Das Phantom in der Mühle, Verlag Klak, Berlin, 2018, trans Eva Wemme; [Leipzig]

Freitagskatze, Verlag Klak, Berlin, 2018, trans. Roland Erb

La gata del viernes, Esdrújula Ediciones, Granada, 2019, trans. Enrique Nogueras

The Book of Perilous Dishes, Neem Tree Press, London, 2022, trans. James Ch. Brown

Arto receptek konyve, Orpheusz Kiadó, Budapest, 2018. Trans. Enikő Szenkovics

Lisoanca, Horlemann Verlag, Berlin, 2013, trans. Jan Cornelius

Lisoanca, Rediviva Edizioni, Milan, 2013, trans. Beatrice Coman

Eliza a los once años, Ediciones Traspiés, Granada, 2014

Lizoanca tizenegy évesen, Orpheusz, Budapest, 2015, trans. Enikő Szenkovics

Eliza, Antolog, Skopje, 2015, trans. Alexandra Kaitozis

Lizoanca, 11 godina, ŠTRIK Publishing House, Belgrade, 2021, trans. Daniela Popov

Zogru, Les Editions du Typhon, Marseille, 2022, trans. Florica Courriol

Zogru, Descontextos, Santiago de Chile, 2018, trans. Sebastian Teillier

Zogru, Balkani Publisher, Sofia, 2008, trans. Vasilka Alexova

Zogru, Bonanno Editore, Rome, 2010, trans. Roberto Merlo

Zogru, Sétatér Kulturális Egyesület, 2014, trans. Enikő Szenkovics

L’omino rosso, Nikita Editore, Florence, 2012, trans. Roberto Merlo

L’omino rosso, Sandro Teti Editore, Rome, 2021, trans. Roberto Merlo

3.2. Chapters, stories in translation

The Ghost in the Mill (Fantoma din moară) (excerpt), in Your Impossible Voice, 2021, trans. Ileana Marin

Cong Quan Shan Dao Ping Yuan De Li Zan, Si Chuan Min Zu Chu Ban She, Sichuan, 2019

The Truancy, The Stockholm Review of Literature

The Phanariot Manuscript (trans. Liana Grama), Trafika Europe, Penn State University Libraries, no. 8, 2016

The Lover (trans. Andrew Davidson), Trafika Europe, Penn State University Libraries, no. 8, 2016

Eliza (Lizoanca), trans. Alexandra Kaitozis, Antolog, Skopje, 2015

Eliza a los once años, Ediciones Traspiés, Granada, 2014 (trans. Enrique Nogueras)

Lizoanca tizenegy évesen, trans. Enikő Szenkovics, Orpheusz Kiadó, Budapest, 2015

Fenerlilere ait elyasmasi eser (Manuscrisul fanariot), excerpt, trans. Leila Unal, Sözcükler, 58, April 2015, Istanbul

Zogru, Sétatér Kulturális Egyesület, 2014, via the “Franyó Zoltán” scholarship granted by the Hungarian government (trans. Enikő Szenkovics)

Lizoanca, Horlemann Verlag, Berlin, 2013 (trans. Jan Cornelius)

Lisoanca, Rediviva Edizioni, Milan, 2013 (trans. Ingrid Beatrice Coman)

Apartment 26, trans. Oana Ursulesku, Koračić, Belgrade, 2013

L’omino rosso, Nikita Editore, Florence, 2012 (trans. Roberto Merlo)

Bill Clinton’s Hand, Bucharest Tales, New Europe Writers, 2011 (eds. A. Fincham, J. G. Coon, John a’Beckett)

Kareli gomlek ve Bukreș'teki Bașka On Hadise (Cămașa în carouri și alte 10 întâmplări din București), trans. Cristina Dincer, Kalem Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul, 2011

I miei ginecologi, in Compagne di viaggio, Sandro Teti Editore, 2011 (trans. Anita Bernacchia) (eds. Radu Pavel Gheo, Dan Lungu)

Ura pri univerzi, Zgodbe iz Romunije, Sodobnost International, Ljubljana, 2011

Zogru (trans. Roberto Merlo), Ed. Bonanno, 2010, Rome; Catania

L’omino rosso (trans. Roberto Merlo), in Il romanzo romeno contemporaneo, Ed. Bagatto Libri, 2010, Rome

Zogru (excerpt) and biobibliographical presentation, in 11 books contemporary Romanian prose, Polirom, 2006, trans. Alistair Ian Blyth

Zogru (novel), Balkani Publishing House, Sofia, trans. Vasilka Alexova

Învingătorul (The Victor) — anthology of the magazine Nagyvilag (trans. Noémi László), Budapest, Sept. 2010

Cristian (French trans. Linda Maria Baros), Paris, Le Bateau Fantôme, no. 8, 2009, ed. Mathieu Hilfiger

Cristián (trans. Sebastián Teillier), Madrid, El fantasma de la glorieta, no. 16/2008

Cristian (trans. Alistair Ian Blyth), ICR anthology, 2011

The Beginning (poem), in Under a Quicksilver Moon, 2002, USA, Library of Congress

Dictionary of Symbols in Mircea Eliade’s Work (excerpt), in La Jornada Semanal, nos. 455–456, 2003 (trans. José Antonio Hernández García)

After the monograph Doina Ruști as a Character in Her Own Book by Pompilia Chifu (doctoral dissertation).

Doina Ruști. Critical Bibliography and Studies on the Work of Doina Ruști. www.doinarusti.ro/despre.html#_biblio, accessed in 2025.