What could you buy with six thalers in the year 1780? First of all, a Turkish saddle made of good leather, adorned with studs and tassels. An ordinary cart also cost six thalers. Sometimes even a slave could be purchased for that amount. Five thalers would buy you a kilo of fine coffee, known as “French.” A turkey might cost two thalers, while fresh river fish could reach ten bani per kilo.

Six thalers was what the schoolmaster Marin spent on a book.

This schoolmaster had just turned twenty-six and was worrying about his future. He taught at Colțea, but most of his income came from Ioniță the butler, whose son took private lessons from Marin.

In addition, he copied books and sang in the choir of Colțea Church — in fact, he was the leading voice, which entitled him to a small coin from the Sunday alms.

Schoolmaster Marin’s great passion was geography. He longed to travel, to roam the world on foot. Sea voyages fascinated him most, even though he had never seen the sea and had no idea what it meant to board a ship. Still, he dreamed of being a ship’s captain, a pirate, a man of the waters. This desire stemmed from an atlas he had bought for six thalers: a volume of world maps printed in Leipzig in 1742.

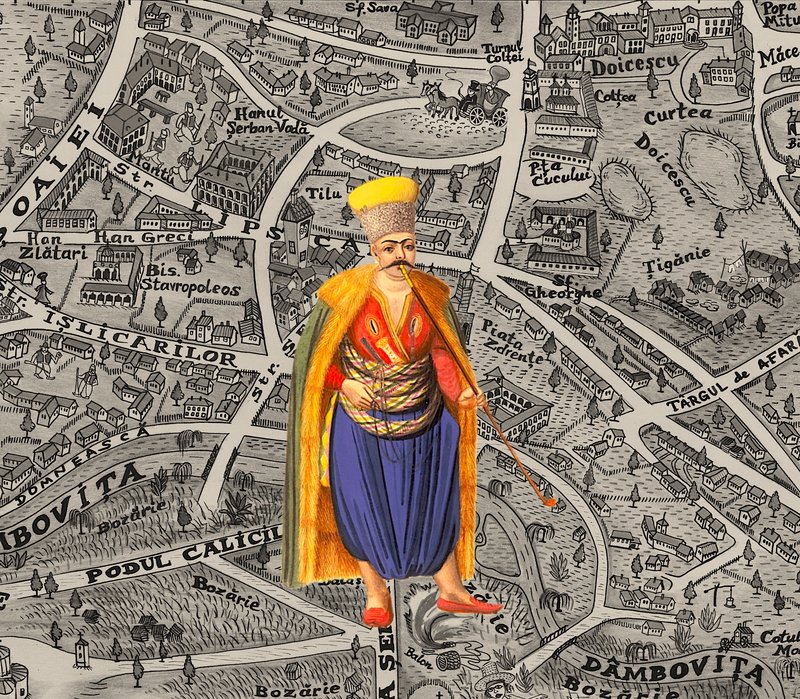

First of all, the atlas allowed him to see the entire world at once, with its oceans dotted here and there with sailing ships, the names of countries and major cities clearly inscribed. When he let his eyes rest on the maps, he felt as if he were flying over borders. Sometimes he imagined traveling up the Danube to Budapest and beyond. He saw himself running through forests or bathing in the Rhine and in other waters whose names he had only just learned. He would have spent all day with his eyes on the atlas, had he not been obliged to go to school.

Yet even at school his passion came first. He rushed through the Gospel passages and opened the atlas, setting his pupils to draw maps — first copying the contours from the book, then urging them to draw maps of their own streets and of the city itself.

A true fever of geography sprang up around the teacher, and the boldest pupils drew their own courtyards, with barns, garden paths, and the hidden corners of their cellars.

His passion spread like a contagion, especially among the students, for teachers often infect their disciples with enthusiasm, even when many are not destined to share such a passion. And once infected, they remain bound for a long time to the teacher’s dream, unable to break free, even when that dream proves useless to them.

Schoolmaster Marin was a man of the book of maps, and no one dared touch it — it was the most important part of his life. In fact, he had written a curse inside it, known to every pupil at Colțea: whoever found the book and returned it to its owner would receive a colac, while anyone who stole it would be condemned to suffer the punishment reserved for thieves of sacred objects.

That curse deserves explanation. First, the reward: the colac offered to anyone who helped recover the atlas was a large sweet loaf, closer to a festive cake, decorated with ribbons, small coins — sometimes silver ones — and candies. It was no trivial reward. But anyone who even thought of stealing the book would not face a mere thief’s curse, but one reserved for sacrilege and defiance — meaning hell, with its harshest torments.

The pupils understood and respected Schoolmaster Marin’s passion. Or else they believed in the power of the curse.

Still, on a Sunday in 1781, the atlas disappeared.

At first, Marin waited patiently, preparing loaves which he displayed in the window so everyone could see they were worth the praise — lavishly adorned with money, especially thalers, and first-quality halva. Then, losing hope, he began to draw maps. First the world map, which he knew best, then the map of the country and of Bucharest. He filled pages and colored them. Encouraged by the pupils, he even drew a mysterious map on the wall of Colțea Church, which provoked widespread discontent. The wall was scrubbed and repainted at the expense of the neighborhood residents, who added a curse of their own for anyone who might defile the holy building again.

But Schoolmaster Marin’s sorrow could not be extinguished.

He drew another map on the wall of his own house — something that, seen from the street, resembled a devil’s head or a horned monkey.

People began to look at him askance, considering him unhinged.

At school, too, forgetting his textbooks entirely, he spoke only of maps — of mysterious places where treasures were buried, of cities whose maps revealed at first glance the source of their power. These were settlements unknown to anyone, places where one might attain supreme wisdom, others that bestowed beauty or heaps of gold. But there were also places where one lost one’s reason or desire to live. Bucharest itself, in Marin’s view, was a city of thieves, and on his map the houses of its most dangerous inhabitants were clearly visible.

Whenever someone mentioned a quality or a worldly desire, the schoolmaster would draw a map, claiming that the key to that aspiration lay there.

As a result, he was dismissed from the school. The community turned against him. Of the respected teacher, nothing remained but the wreckage of an unlived adventure.

Even so, the people of Bucharest acknowledged his passion, calling him The Geographer of Colțea — a name preserved in folklore for over two centuries. Many people took up the habit of drawing maps, marking the city’s main points. Shops began selling scarves embroidered with maps. For a short time, there was even a street called Geographer Street. Some of his former pupils ordered atlases and geographies, and from the eighteenth century date the first more respectable maps of the city.

As for me, I found his name written in an old atlas, printed in 1742, where a steady hand had once inscribed:

“This book belonged to the Geographer of Colțea, long dead, and I bought it for two thalers at the Outer Market, from Mitu the horse trader, son of Ioniță the Butler.”

10 October 2023, Adevărul, republished on doinarusti.ro