In a document dating from the late seventeenth century, one finds recorded a wine recipe worth remembering. Into freshly pressed must, a small pouch made of fine cloth was placed, containing the following plants: two handfuls of lauruscă flowers, carefully dried in the shade; the same quantity of elderflowers, also dried; and crushed coriander seeds—crushed, but not ground into powder. The must would ferment and turn into wine, absorbing the miraculous properties of these plants. The entire process lasted ten to twelve days, and the quantities were calculated for a barrel of ten vedre. The barrel was sealed and kept for important occasions.

This wine could be sold at a good price.

Some Bucharest merchants stored it in their cellars and sold it as imported wine; others offered it to well-to-do ladies as a love remedy. Most released it onto the market after the winter holidays, when ordinary wine had run out, in order to fetch a higher price.

Among those who knew this recipe was the daughter of a grocer from Lipscani. Unlike the others, she knew exactly when the lauruscă flowers had to be gathered.

For those who may not remember, lauruscă is wild grapevine. It produces small, rather sour grapes, and in my childhood there was such a vine in our garden, cultivated especially for its flowers. I remember them well: a white inflorescence, a cluster of tiny blossoms, related to elderflower. When dried with care, these flowers develop an aroma that invites dreams and amorous reveries.

The grocer’s daughter knew the paths and varieties of vine intimately. She even had a particular bush, near the entrance to Andronache—a very old vine that, on a certain day in early June, began to spread around it a fine vapor, a living mist, upon which desires never before attempted would sway.

Clinging to oak trees, the vine was so old that its trunk had thickened like that of ancient trees and had spread over a considerable area. Foxes and hedgehogs made their dens beneath it.

The grocer’s daughter would fill her bag with the fragrant clusters and head home, unaware that an old god, wrapped in perfumes, was following in her footsteps.

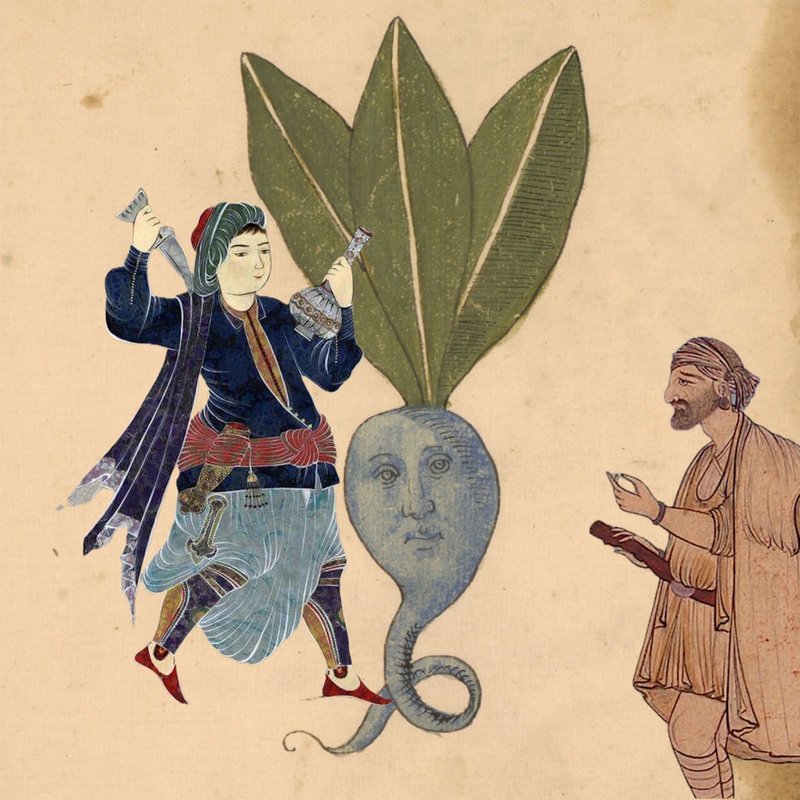

Long ago, he had belonged to the retinue of the Bacchae, accustomed to dancing among vine tendrils. But as the gods changed and his Bacchae disappeared altogether, the small god remained forever bound to a grapevine—the ancestor of the one in Andronache.

At the beginning of summer he accompanied the grocer’s daughter, spending the warm months in the shade of a cherry-plum tree and between the windows of her house, where she kept the fragrant flowers. And in autumn, when it was time for wine, he joyfully entered the barrel. This was the happy part of his existence. For several months he lived dionysiacally, fully and without restraint.

In February, when the girl sold the wine, recalling the Anthesteria of his youth, the frail god would scatter into the glasses some of his oldest desires.

In February 1741, Bucharest was struck by an unusual plague. The most hidden desires took to the streets. Women who until then seemed destined for convent life began slipping out of their houses at night to indulge themselves. The wife of an armaș stripped naked in broad daylight and crossed the street to the grocer’s shop, where the girl—an enthusiast of vinous delicacies—prepared a new flask for her. In the attic of the Saint Sava Academy, young women of good standing were discovered drinking heavily. Several men were caught in bedrooms where they had no business being. Divorces followed, and the Metropolitan compiled a list of the city’s debaucheries, complete with names and addresses, ready to read it aloud. But there were also many weddings, passions, and loves worthy of being recorded in chronicles.

All these events, as you may have guessed, were linked to the wine prepared by the grocer’s daughter. She herself had lost her balance, for whenever she descended into the cellar to prepare a flask for sale, she would be overwhelmed by wild desires.

And what was strange in this story was that night after night, the customers—women and men alike—shared the same dream, which soon spread throughout the city. Everyone dreamed of the small god, who took on many forms, shifting easily from the face of an ephebe to the sly expression of a man worn down by boredom. Despite these metamorphoses, everyone knew who he was, and the entire city adored him.

In markets, beneath inn staircases, in cafés, or on Filaret Hill, townsfolk exchanged dreams, competing to describe the beloved god. Toward the end of February they even dedicated a song to him, preserved for a long time among the pages of a gospel and partially reproduced by the pitar Deleanu on the back of a painting. From there we learn that he was young and a fine dancer, that he loved lauruscă flowers, from which he knew how to weave garlands.

As the events repeated themselves year after year, and as the grocer’s daughter now ran the most profitable business in the city, the people of Bucharest accepted the existence of this winged god, who still spends his springs in the same wild vine and his winters in the wine barrel. Some call him Dragobete. Others call him the lover from the dream.

The original Romanian version of this story was published in Adevărul and can be read here.