“The Ghost in the Mill” and the World of the Living Dead.

On a Critical Essay by Elena Crașovan, professor at the Faculty of Letters, West University of Timișoara.

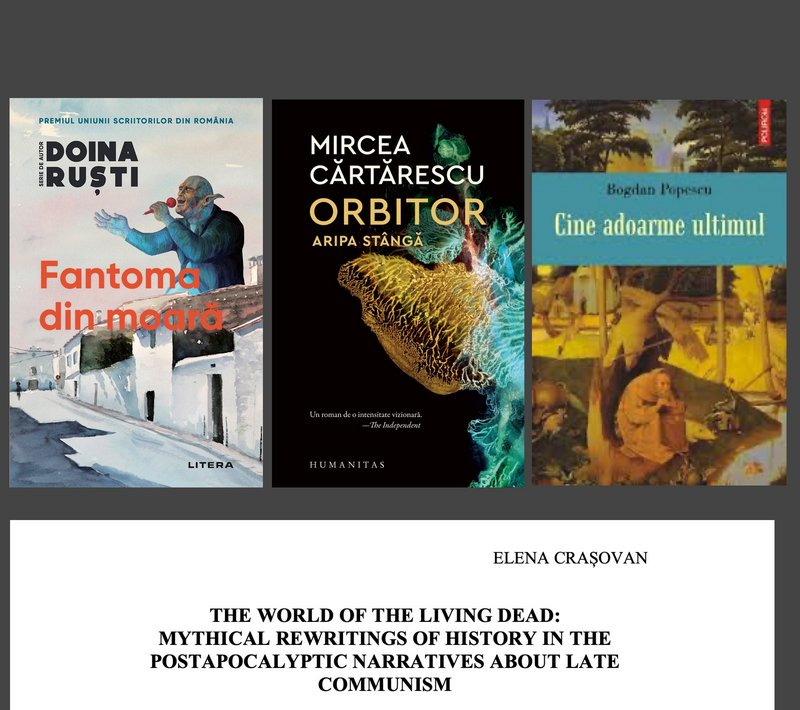

In a study published in Dacoromania litteraria (2017), literary critic Elena Crașovan offers a comparative reading of three Romanian novels about late communism:

Blinding. The Right Wing by Mircea Cărtărescu,

Whoever Falls Asleep Last by Bogdan Popescu,

The Ghost in the Mill by Doina Ruști.

Her central claim is that these books do not simply “tell” the story of communism, but mythically rewrite history. They do so by using apocalyptic scenarios, ghosts, and magical realism as tools to explore collective memory. Within this framework, “The Ghost in the Mill” occupies a key position, as the novel in which the ghost most clearly becomes a metaphor for a past that refuses to stay buried.

For Crașovan, the village of Comoșteni is a double space:

on the one hand, it is the landscape of childhood, rituals, local myths, and everyday magic;

on the other, it is the stage upon which violent, dehumanising history unfolds.

The mill – “the heart of the village” – appears as an ambivalent symbol: a source of life and, at the same time, a devouring machine. Its destruction in the 1980s is read not as liberation but as a false apocalypse: the past is not settled, only shattered and dispersed into the bodies of the villagers, who become permanent carriers of trauma.

Crașovan’s most striking observation concerns the transformation of the ghost:

this is not a classic apparition haunting a place, but an invasive force entering both body and mind.

For the characters in The Ghost in the Mill, the encounter with the ghost is experienced as:

physical aggression,

a violation of intimacy,

and, at times, a sickly form of love or dependency.

Victims and agents of power, poor villagers and representatives of the regime, all share the same condition: possessed bodies, lives lived with “someone else inside.” This leads Crașovan to speak of a “world of the living dead” – people who continue to perform daily gestures but no longer feel in control of their own destiny.

Another key concept in the essay is “reversed nostalgia” (borrowed from Svetlana Boym):

not longing for an idealised past, but dreaming of a future moment when someone else will finally fix everything.

In this light, the novels under discussion – including The Ghost in the Mill – portray:

communities trapped in an endless transition,

characters who no longer believe in their own agency,

a world in which history is felt as an impersonal force that simply happens to people.

In Ruști’s novel, this idea is embodied by the inhabitants of Comoșteni, who come to see themselves not as subjects of their own lives, but as figures inserted into a story written elsewhere.

Crașovan insists that magical realism in The Ghost in the Mill is not decorative, but a way of representing:

what cannot easily be named,

what is too painful or obscene in the history of communism.

The ghost, the mill, the contaminated village, the possessed bodies – all of these function as figures of memory, turning an unspeakable past into images, atmosphere, and local myth.

The study also points to a paradox: although these novels adopt an apparently “post-apocalyptic” vantage point, as if history were already over and fully understood, they actually testify to the impossibility of truly closing the past. The ghosts do not leave, the apocalypse clarifies nothing, and post-communist communities remain suspended in an in-between time.

Even though Crașovan’s interpretation emphasises passivity, devitalisation and “living dead”, it has the merit of:

placing The Ghost in the Mill in a major critical dialogue with two other landmark novels on late communism;

highlighting the metaphorical power of the Ghost as a figure of history entering and inhabiting people;

showing that the novel’s magical realism is not escapist, but a way of engaging critically with the past and exploring collective memory.

For today’s readers, this perspective offers a useful key: The Ghost in the Mill is not just the story of a haunted village, but the story of a society trying to live on with its own historical ghosts.