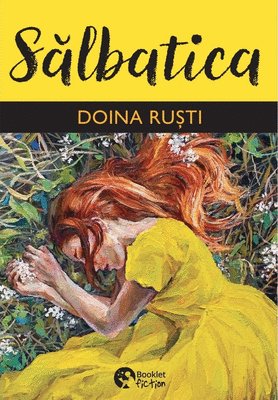

Doina Ruști

The Wild Girl

I. The Encounter

It all began one morning when I went to catch quails with Dad. On Sundays, he’d grab the nets and say, “Let’s go, Tavi, before their season ends, and we can kiss goodbye to such delicacies.”

I wasn’t keen on quails and liked to chase them even less, but for his sake, I’d put on my pants and adjust my cap—I can still picture myself wearing an oversized cap Mom had tightened to fit my head. She had sewn a button at the back, which made me look like an old-time soldier, and would even tease me, saying, “Tavi, when you hold the drum, you look like a character out of a movie!”

So there I was, cap perched on my head, walking half a step behind. We had reached Lutu Alb, a fetid marsh, and still had a long way to go. Dad was whistling away, the nets draped on his shoulder, and I was absorbed in my thoughts when I saw her—a yellow spot amidst the dry reeds. I stopped, expecting Dad to do the same, but he carried on, his eyes fixed on the sky. The moment I turned to look at him, the spot had vanished. I kept quiet, but the sight left me feeling uneasy. I turned to check that no one was following us and saw her again. She had crossed the path and entered the millet field. That was when I let out a shout and started chasing her. I ran through the millet stalks and saw her slithering like a snake, avoiding the bare patches, so I was sure it was something small, maybe a fox or a dog, a shadowy figure with a yellow cloth trailing behind. She escaped into the open field beyond the millet crops. There was nothing in sight, just the land laid bare, like a freshly cut slice of bread. Where could she have disappeared?

I turned back because Dad was calling me, rooted to the path. Judging by his expression, I could tell he was annoyed.

“There’s nothing there, Tavi. Don’t worry.”

I recounted the event to the best of my ability, emphasizing the color and size, but he just laughed. Only in the evening, when we returned with the quails, did I hear him tell Mom:

“Just you wait, Marcela. Next time we'll bring you a bustard. Tavi saw something by the marsh slipping into the millet field. Said it was yellow. Maybe the bustards are back. I haven't seen one since I was a child.”

Mom doubted it, saying she had seen a dog being made fun of, wearing a burnt orange vest.

“There are some very unruly kids who torture animals. They’re neighbors with Mișu, who’s a menace himself. Did you hear me, Tavi? Stay away from him!”

A string of monotonous days ensued. I remember they called us to school to carry firewood. A truck loaded with winter logs had arrived, and the principal had hired someone to cut them in the courtyard with a saw. We took them by armfuls to the storage room.

“Keep it up, children!” the principal encouraged us. “Think of how cozy we'll be this winter!”

After we spent the morning moving firewood, he suggested we sweep the ground since we had already made the trip to school. So, we grabbed some dried blackthorn branches, perfect for raising the dust to the tops of the mulberry trees. And how should I put this, in the Bărăgan Plain, life is half made of dust.

On that day of sweeping and carrying firewood, the boys and I headed to the marshes. Among us, Mișu, whom Mom didn’t particularly like, was the most well-traveled. He roamed a lot and had even reached the Traian manor house, where he found various things, including a book he lent me. It was the most captivating read I had ever had and my first novel, a book unlike any other, with characters and events that are still etched in my mind—The Count of Monte Cristo. I ended up with the impression that this manor house at Traian was some sort of wonderland. It was said to have belonged to a man from the old days, a boyar or a wealthy peasant, or whatever he might have been.

I was walking with Mișu behind a group of boys, and we were scheming to sneak off to Traian when I saw it again. It was around the same place, by the edge of Lutu Alb, and this time it disappeared into the water.

“That's an otter, Tavi,” my friend said. “As soon as you see one, you must whack its head. If it starts breeding, it'll come after the chickens and won’t stop until it eats them all.”

“Yeah, right!” I snapped. “Didn't you see the yellow rag on it?”

“It must’ve got caught in some tatters. Don't worry. If it were a monster or something, it would’ve come up for air by now.”

Still, my heart was pounding, and I hoped he was wrong because I was ready for feats and adventures that summer, like in the movies.

We sat by the marsh for a while, hoping it would emerge. Mișu had a cigarette he'd stolen from his dad, and we passed it back and forth, choking on the smoke like champs. I could sense that the yellow apparition was lurking somewhere behind the cattails, since the marsh was overgrown with weeds and reeds that summer. We stood up to leave, and I felt like someone was watching us. We were loud so it could hear us, and I was making a spectacle of myself to impress that otherworldly being. But no one called out to me. Not a single ripple disturbed the water. Mișu rummaged in his pockets and extended his palm.

“Check this out! Ever seen a coin like this?”

It was a small golden coin with a man’s face, his hair neatly combed.

“Maybe it’s Comrade Stalin,” I guessed.

“You're an idiot. Can’t you see it's Romanian? And look at the year: 1930.”

I knew where he’d gotten it—from the enchanted manor house, which had become a place I had to visit.

“How long to Traian?” I asked, eager to set off right then.

“We could take the train, but we'll have to wait for it, and if the conductor catches us—you're paying. It's better to cut through the fields; it’ll take less than an hour. But I can't go today. I'll tell you when.”

Trans Alina Gabriela Ariton

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/2919952.DoinaRuti