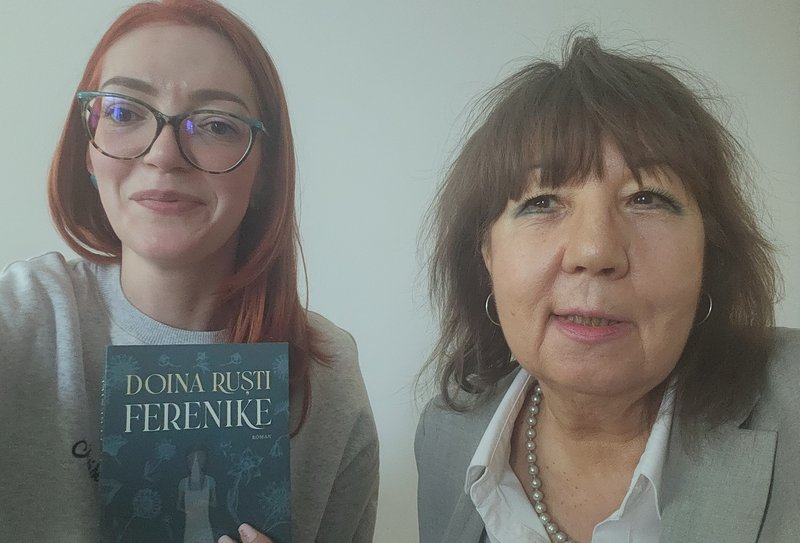

Today I came across a confession—one that still follows me—which I gave not long ago to Ioana Zenaida Rotariu. She had asked me something about writing and fiction, and I replied.

Zenaida Rotariu: “I hated her [Muc] for her brutal honesty, while I adored Cornel, who lied to me in an artistic manner.” Who are Muc and Cornel? Do you still see them today the same way the five-year-old girl once did?

Doina Ruști: Muc and Cornel are my parents, who died young, before they had fully matured, and I will always see them at the age they have in the novel—the only age I ever knew them. They do not appear through the child’s perspective, but through that of the mature narrator. My various ages are permanently connected, exactly like the forms of a word passing through its metamorphoses. For example, whenever I say avatar, I think of all the plural forms I’ve used throughout my life.

In my youth, I used the Eminescian plural avatarii, which was then common among the educated. It was pushed aside in the ’80s, when the dictionary form avatare became dominant. And after ’85, when preserving Latin-inherited suffixes became a linguistic topic, it aligned with the other “made-up” neuters and turned into avataruri.

All these forms point to an evolving experience and a social history. Whenever I say avataruri, the other forms come to mind—together with Eminescu’s prose, with my earlier selves, even with certain items of clothing—three nominal forms, effervescent, on the verge of dissolving, passing from mouth to mouth. Three forms of the plural, exactly as they should be—caught in a complex historical metamorphosis.

Exactly the same with my ages: though interconnected, each carries its own distinct charge. So I return to Muc and Cornel from my current perspective, to link them to my other ages, including childhood.

Cornel is the main character, while Muc is more of a reflector-character here, and that is natural, because Fereniketells the story of my first life experience, forever tied to my father—to the novel’s central story. I avoided the classical approach, with the father figure in the foreground, and instead chose a character who belongs to my writerly imagination. In the reality of my childhood, Cornel was a young man in the process of adapting to the world. Immature and a poet at heart, he was my gateway to learning the paths of adventure. In Ferenike, he becomes the protagonist of my adventure—an adventure taken seriously, viewed now as the natural road of fiction.

Not once did I step into the child’s skin; I did not adopt naivety as a narrative mode. Symbolically, Cornel represents the fabulous side of the imagination, for we must admit that in the realm of artistic “fabrications,” there exists both a reparatory imaginary—which turns the character into a hero (positive or negative)—and a long-distance imaginary of messages.

Both are grounded in the deceptive abilities of human beings, which is why I insist here on the fabulist side of my character. Cornel is the artistic liar who, at one point, opens the door to fiction for me. I did not pursue family relationships; I was not interested in the father–daughter dynamic. In this novel, the main character is me—

the capitals of my life.

The rest can be found on LIBRIS.