The eagle, sometimes called pajură or vultur, represents a protective spirit of the world, both as a state emblem and through its mythological role in Romanian imagination. Its oldest name is zgripsor, used both for the fabulous bird of fairy tales and for the Wallachian heraldic eagle. Even coins, which bore the eagle engraved on one face, were long called zgripsori, as Nicolae Filimon’s novel attests.

From the medieval period onward, the word was strongly rivaled by pajură, borrowed from Polish. Yet zgripsor—although it echoes the Greek form gryps—remained deeply rooted in the lexical imagery through a series of derivatives associated with the strength of talons, from which the very name zgripsor derives, as Șăineanu explains. He points to verbs with the meaning of scratching or seizing with claws—a zgrepța, a zgripțâna, a zgrepțora—all part of the same word family. Among heraldic symbols there is even one representing only two crossed claws, like invincible weapons. But on the coat of arms of Wallachia, the zgripsor traditionally appears as a watchful bird, or with wings spread, always single-headed.

The eagle is one of the essential archetypes of the Mediterranean world, and for Romanians it may be regarded as a totem with archaic roots. As a heraldic sign, widespread in Europe, the eagle symbolizes power and nobility, embodies divine virtue, and is seen as a warlike, protective bird. On the coat of arms of Wallachia it is depicted with wings open, in an offensive stance, with emphasized vigilance. It first appeared on a coin minted by Vlaicu Vodă (1368), later adopted on a seal of Mircea the Elder in 1390, where it holds a cross in its beak and gazes toward a new moon embracing the sun.

Interestingly, on Dacian coins discovered so far, an eagle often appears, quite similar to later depictions on the Romanian coat of arms, holding a crown in one claw.

In Romanian imagination, the zgripsor, zgripțor, or zgripțuroaică is a gigantic bird dwelling in the Otherworld. Only through it can the fairy-tale hero return to the realm of flesh and perishability. Descending is easy, usually by slipping to the bottom of a well or abyss; ascending is nearly impossible. Here the giant bird intervenes, flying back to the human world with the daring traveler on its back. It is no philanthropist—it helps the lost hero because it is a bird of honor. In many tales, Făt-Frumos, Prâslea, or another prince discovers in the Otherworld the zgripsor’s nest threatened by a dragon. He saves the chicks by slaying the dragon with his sword, and in gratitude the bird carries him back to the realm of normal life. The bird is greedy, carnivorous, ready to devour any human who trespasses on its territory, yet it always shows goodwill toward the savior of its young.

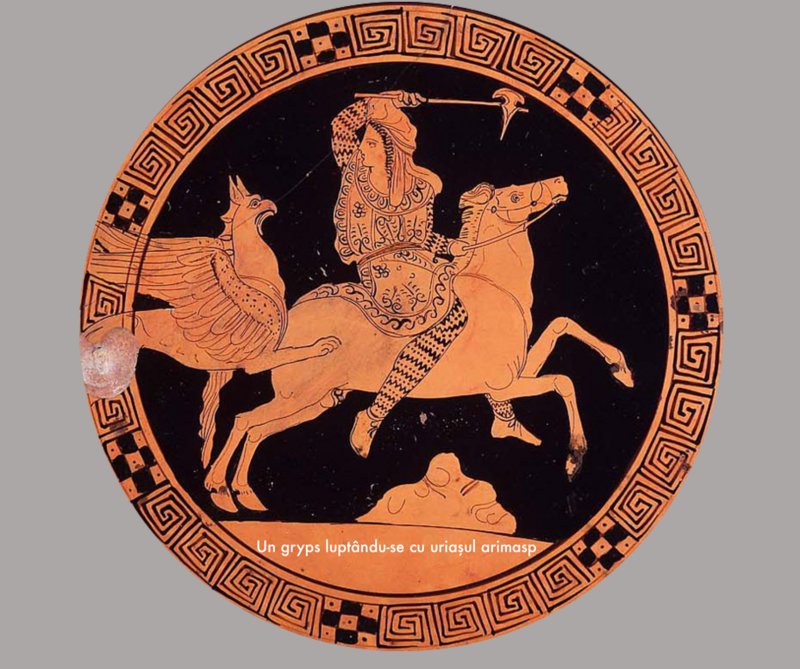

Thus the zgripsor is a monster dwelling in the underworld, in eternal conflict with the serpent. As in numerous Byzantine representations, the serpent or dragon is the traditional adversary of the giant eagle. As if bound by fate, it always builds its nest near a spring or fountain inhabited by a perilous dragon. This epic tradition comes at least from Greek antiquity, from tales of a giant bird with lion’s claws and an iron beak, called gryps—source of the Romanian form. This bird guarded the gold of northern Europe and was often attacked by the Arimaspi, a people of one-eyed giants believed to live beyond Scythia, in mountains many historians (including Pliny the Elder) identified with the Carpathians. A poem attributed to Aristeas tells of battles between the grypses (later known as griffins) and the Arimaspi, who rode winged horses into Hyperborea. Aeschylus calls the grypses the “dogs of Zeus,” fixing them in the same region, and in pictorial representations they appear as winged lions. On a vase painted by Pasitheia around 400 BC, the gryps resembles more closely the Romanian zgripsor: it is shown as a giant eagle drawing Dionysus’s chariot. Its powerful beak is emphasized by realistically painted plumage, with a spiky crest on its head; the claws, however, remain those of a lion.

The ancient accounts emphasize above all the gryps’s role as guardian. It stood at the gate of Hades’ dark world and kept watch over gold. From here perhaps arose the link between the zgripțuroaică and the dragon—also a guardian of treasures—as well as her dwelling in an underworld, often called in fairy tales the Otherworld. This is not the paradise beyond death, but a bewitched, inaccessible place. In Ispirescu’s fairy tale Prâslea the Brave and the Golden Apples, the zgripsor lives at the bottom of the abyss, where everything is transformed—earth, flowers, trees, and creatures made differently. In this world are gathered all magical objects: the whip that alters dimensions, the hen with golden chicks, an enchanted spindle, flying slippers, and so on. The undisputed rulers of this world are the winged giants called zmei—vague archetypes of the Arimaspi, though not depicted as adversaries of the giant bird. Indeed, it has but one enemy: the ruthless dragon, whose death signifies ultimate good. Once rid of the dragon, the bird is seized with such joy that it could swallow its benefactor whole from sheer enthusiasm. Life without the dragon’s threat flows so smoothly that the zgripsor sets out on a long journey to the human world, a journey lasting as long as twelve or twenty meals. Laden with bread, meat, and water, carrying on its back the man who saved its young, the gigantic bird travels from the underworld of eternity to the world of ephemeral life. It is a nightmarish creature, able to cross spaces traversable only by winged horses or zmei. Unlike them, it has no ties to the mortal world, does not attack humans, nor does it serve them consistently as the enchanted horse does. The zgripsor makes an exception only for the savior hero, whom it embraces affectionately at parting.

Generally, the bird serves as courier and is associated with time’s swift passage and with death. This monstrous prototype is a sort of “sole of hell,” hence also called zgripțuroaică: an impetuous being, ready to swallow anything that moves—out of joy or out of need. After the dragon is slain, the zgripsor’s chicks send their mother in all four directions to search for their savior, and only once her enthusiasm subsides do they reveal he was hidden beneath a feather in their nest. Her lack of self-control and gluttony mark her as a figure of devouring time. For this reason, proximity to the time-ravaged world unsettles her, stirs her appetites, and compels her to return swiftly to the underworld. Paradoxically, though dwelling at the bottom of a chasm, she remains a solar, combative bird, nesting atop a mountain so she may touch the sky. Her size matches her chosen domain: in one tale it is said that her chicks are as large as three bustards, which means she herself is downright gigantic, sovereign over vast horizons.

The giant bird of myth or the eagle of the Wallachian coat of arms synthesizes elements of an archaic totem. She links worlds, unites sun and moon, is winged and armed with merciless claws. Mistress of wide domains, unpredictable, vigilant, the eagle is also tied decisively to geography. It is possible that the original prototype was the lesser spotted eagle (Aquila pomarina), once common in Wallachia, especially in marshy regions. Dimitrie Cantemir suggests this. In his Hieroglyphic History there is a character, architect of intrigues yet also sage of the ruling clan, embodying the stolnic Constantin Cantacuzino, known as the most important Wallachian cultural figure of the Brâncovenesc period. This character is called brehnace—the folk name for the lesser spotted eagle, today extremely rare and legally protected. Cantemir’s brehnace appears accompanied by a hawk and a raven, other birds of prey—a subtle reference to the Cantacuzino coat of arms, which bore the Byzantine double-headed eagle, and at the same time a satirical transfiguration of the Wallachian crest.

Bound to the real world and enshrined in mythic heritage close to Hyperborea (Herodotus, Pausanias), renewed on the banners of Roman legions or by various medieval peoples, the eagle has preserved its mythic power as the hidden bird of the underworld, ready to restore order. She brings home again the hero whom his brothers tried to kill. She restores the lost hero to history. The uncontrollable, impetuous zgripțuroaică, ready to devour anyone, renounces the sweet morsel cut from the prince’s thigh and reconstructs him, rejoining the missing part and healing his wound. For she is mistress of the unseen world and the vehicle maintaining connection with the vast underground of Balkan spirituality.

In folklore, birds of prey are generally protectors of the hero: the raven, the vultures, the hawk sometimes come to man’s aid. Identified with the vulture, the eagle—also called pajură—protects the weak. Commenting on its symbolism, Simeon Florea Marian shows that the popular name for the eagle is vultur. In Justice and Injustice, a fairy tale collected by Ion Pop-Reteganul, the vultures help a blind man and punish the one who blinded him. I. A. Candrea also presents a number of tales in which the vulture, also called pajeră, helps and rewards man.

Literary culture, however, distinguishes between vultur and pajură. Treated heraldically, the symbol appears in Mateiu Caragiale’s poetry collection Pajere. In the opening sonnet, the leaden clouds / Seem pajere locked in the grip of fairy-tale zgripsori.

In a similar sense of a fateful bird—yet recalling the fairy-tale pajeră-zgripțuroaică—we must also understand Nichita Stănescu’s vulturoaica:

I provoked and maddened the vulture-woman,

dead with exhaustion, climbing to the peak.

Instead of clouds, blizzards, blue stars,

I found her brooding on her eggs.

I whistled at her, shouted at her,

I sang to her;

she, calm and majestic, high on the summit,

ruled over the eggs in her nest.

I tried to drive her away,

but she gashed my face with her beak.

I tell you this:

This mountain is not to be climbed,

for there is nothing to be seen!

I tell you this:

Whatever there was to see,

the vulture-woman has already seen!

(Sign 21)

The allegory recalls the fairy-tale hero who climbs toward the zgripțuroaică’s nest, driven by the constant longing to see the Otherworld, to visit or depart from the unseen realm of eternity. Yet Nichita’s pajură is merciless, guarding a world she conquered long ago. This calm and majestic bird is inaccessible, like the history of a totalitarian world from which no escape is possible.